|

G

A H A N

W

I L S O N : Comedy & Horror (excerpted from Locus Magazine, March 1999) | |||

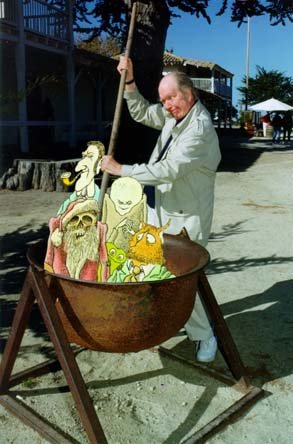

Photo by Beth Gwinn (cartoon by Gahan Wilson) |

Gahan Wilson's work first appeared in Amazing Stories in 1954, but he became nationally known through art in slick magazines including Colliers, Playboy, and later The New Yorker. In 1964, he began a continuing association with F&SF, as cartoonist and occasional reviewer. His long series of graphic art collections began in 1965 with Gahan Wilson's Graveside Manner; recent volumes are Gahan Wilson's America (1985), Still Weird (1994), and Even Weirder (1996). Wilson has done a detective novel, Eddy Deco's Last Caper: An Illustrated Mystery (1987) and a number of children's books, animation for 20th Century Fox in Gahan Wilson's Diner (1973), and the CD-ROM game ''Gahan Wilson's The Ultimate Haunted House'' for Microsoft/Byron Preiss Multimedia. He has written reviews for F&SF and The Twilight Zone, and is currently reviewing books for Realms of Fantasy. Wilson designed the World Fantasy Award, a bust of H.P. Lovecraft, in 1975 and has served as toastmaster and awards judge for several of the World Fantasy Conventions. He won a special World Fantasy Award in 1981, the Best Artist Award in 1996, and was Guest of Honor at the 1998 convention. Wilson started publishing short fiction in 1964, and the best of this work appears in his latest book, The Cleft and Other Odd Tales (1998), along with his own illustrations. ''I find there's no conflict at all between my art and my writing. The more you do, the greater variety of things you try to do, the stronger everything gets. The tricky part is, everything has to be done as well as you can do it. Very early on, I was doing cartoons and I wasn't selling to any of the major markets, because I was really far out back in the '50s. The editors would laugh and laugh and say they were 'great cartoons, kid, but the readers wouldn't understand them.' But I persisted. I realized from the get-go that to get what I was doing into the Saturday Evening Post would be hopeless. ''I was a creepy little kid. I did the whole comic book thing, and then I discovered Weird Tales – instantly homed right in on that around high school, and just loved it. There really wasn't that much fantasy available in libraries, and Weird Tales filled the gap. I really started with the science fiction pulps, and then I spotted Weird Tales and went for that. One of the very first things I did when I came to New York was to go to Weird Tales on the off-chance they'd take a little portfolio. I did get some drawings into Weird Tales, so I just got into the original pulp scene. I was very happy with that. It was really in the nick of time, because the whole damn thing collapsed not long afterward. ''My big break came when the cartoon editor for Colliers – who, like everybody else, thought the readers wouldn't understand the cartoons I did – left to become the cartoon editor of Look. In the interim, the art director took over. Not being a trained cartoon editor, he did not realize my stuff was too much for the common man to comprehend, and he thought it was funny. I was flabbergasted and delighted when he started to buy it! He wasn't in all that long, about a month and a half, but by that time my cartoons had started to appear. The guy who had gone to Look saw them in Colliers, and I guess a great dawning occurred, so he started buying them for Look, and that was it – I was now a big-time cartoonist! Absolutely foolish, but that's the way it happened. That was the chink in the armor, and I just got through it. ''Obviously, Charles Addams was a huge influence on me. I particularly loved the period in the '40s and early '50s, when he had this very neat, detailed, precise, almost Byzantine style, combined with a fantastic sense of atmosphere. ''A lot of the Playboy cartoons are an absolute hommage to Lovecraft's stuff. In one, a flasher spreads his tacky raincoat and horrifies a little old lady and her dog in a park, and he is not exposing human anatomy – the knowledgeable would know it was Wilbur Whateley of 'The Dunwich Horror'. And I did a whole spread on Poe for Playboy. We realized most people don't really know Poe. They think they do, but they've only read three or four stories. So Ray Russell said, 'Look, I'll write an introduction to it, and I'll throw in the titles of these things.' I did endless numbers of Sherlock Holmes cartoons, including a great big spread, and I was extremely flattered – I was invited to a Baker Street Irregulars dinner, and they took the whole thing and made it into their menu. That was high praise indeed! ''One other interesting thing: in a puritan society such as ours, if you do humor or horror in any artistic thing, it is automatically considered to be less than if it's 'serious.' If it doesn't scare you and it doesn't make you laugh, it's 'serious.' If the artist gets scary or he gets silly, the critical tendency is to say, 'That's a minor work.' So it was a bitch for Edgar Allen Poe or Mark Twain to get serious recognition. They finally managed to do it, because they did some of the best stuff around, but it was an uphill struggle. ''Art should lead to change in the way we see things. If some artist comes up with a vision which gives a new opening, it usually creates a lot of stress, because it's frightening. Like Cubism reveals there's this whole other reality to reality, or Stravinsky comes along, and there's a riot! This is art. It's very disturbing. If you really see a Cézanne, you never see anything the same way afterwards. It's heavy stuff, very powerful. And the artist – literary, graphic, or whatever – does an amazing thing. The creative artist is automatically an outsider, because he sees through the world that everybody else takes as the final reality, and he's a very scary kind of guy." |

||

| © 1999 by Locus Publications. All rights reserved. |