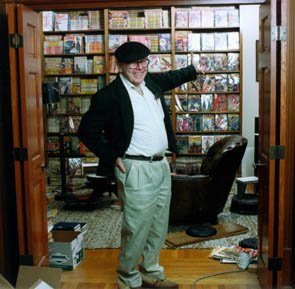

Frank M. Robinson is also considered one of the foremost collectors of pulp magazines, with probably the only near-mint near-complete collection extant. He has written two illustrated histories: Pulp Culture: The Art of Fiction Magazines (1998) and forthcoming Science Fiction of the 20th Century: An Illustrated History. He lives in San Francisco, California.

I visited Ray Palmer, editor of Amazing Stories, up in his offices, and of course I was totally awed and impressed – I was 16 years old. I used to talk to Palmer about writing science fiction, because obviously that's what I wanted to do. He was editing his magazine for younger readers, and his advice was, 'When the action slows down, just throw another body through the skylight.' The other thing he said was, 'When you get through with a story, always go through and every place where you think there is consciously a bit of good writing, cut it out.'

''The best science fiction is a literature of ideas. SF has always used story structure to get across basic ideas, even though most of the ideas were sheer crap. In a 1930s Astounding editorial, F. Orlin Tremaine said he wanted the magazine's letter columns for scientists to test out their theories. Ridiculous! It's a 20¢ pulp magazine, and he thinks Einstein and other people are going to write articles! Tremaine was more intent on putting science in his stories than Gernsback was. It shaped Astounding to such a degree that John W. Campbell never forgot that. Tremaine started running science articles, most of them written by Campbell, and when Campbell became editor, he continued the process. And he continued pushing amateur science, in this case a lot of crackpot theories.

''What wasn't realized at the time was that sociology and psychology could be treated as sciences. The guy who started that awareness more than any other was Heinlein. Heinlein treated politics, sociology, psychology, as science. This was the introduction of a scientific idea in the service of adventure. Heinlein could write about a future that was so real, you could walk around in it.

''I went to grad school at Northwestern, took another course in fiction writing, and I wanted to do a superman story. I vastly admired both Stapledon's Odd John and Norvell W. Page's Not Without Horns. I had heard of a jump rope rhyme concerning 'the man with the power.' I used a science fiction theme, but with a mystery/suspense development which, to the best of my knowledge, had never really been done before.

''I finished The Power, got an A- on it, and it sold first crack out of the box, to Lippincott, for the munificent advance of $500. That was a tremendous amount of money. The Power did very well for that time – sold 8,500 copies. Back in 1956, for this kind of book, that was damn good. Film options started to come in – one of them from a film student named Francis Ford Coppola!

''The Power was appealing to filmmakers because it's the most elementary, basic form of suspense thriller there is. Someone summarized a great suspense story as 30,000 words of 'You chase me,' and 30,000 words of 'I chase you.' People like those for movies because they're easy to do, simple to understand, and all you need is that certain little twist to differentiate it from the others.

''By the time The Power was made into a movie in 1967, I was living on poverty row in Los Angeles. I went to see the movie at the bottom of a double feature, and I walked out in the middle of it.

''The guys at Playboy called me up and asked me if I would interview Robert A. Heinlein, who lived right down the peninsula. They sent out a photographer and we went down to visit Heinlein, who put us up in a guesthouse for three days, and I talked to him. I thought it was a great interview, a great insight into the man. But then the Manson murders happened, and Manson reportedly patterned his life after Heinlein's character Michael Valentine Smith. Hefner wanted Heinlein to comment on that, and Heinlein refused, so Hefner killed the interview. A portion of it, less than half, eventually ran in a companion magazine, Oui.

''This sounds pompous and pontifical, but in The Dark Beyond the Stars, the real subtext is the value of life. Life itself is probably very rare, and in this world we treat it so casually because we're surrounded by it. You can't pick up a rock without discovering life. We have no real respect for it, no admiration. If we were starving men, a little bit of food would be a magnificent feast. If we really knew what the entire universe was like, life would be a total miracle. That's what I was trying to get across.

''Waiting has essentially the same combination of concept and suspense. The great mystery in modern anthropology is 'What happened to the Neanderthal?' The idea of genocide was being bruited about. I noticed there were a couple of different branches of Neanderthals. The European branch was a species modified by weather. Eskimos today show many of the same external features – large torso, short nose, broad limbs. But there was another branch of Neanderthals that lived in the Levant and came very close in appearance to Homo Sapiens. I thought, 'Wait a minute. What about the possibility of them trying to pass?' In which case, they might have survived.

''I first got into the history of the SF field in Pulp Culture, and that came from my collecting habits. I used to be a science fiction collector – when it came to the old magazines, only science fiction – and I built up a tremendous collection of magazines in near-mint condition, which means thousands of dollars, thousands of hours looking for them, and then taking very good care of them. Then one day I went over to the Locus basement, which had Adventure magazine, which I'd never really seen before, and I fell in love with Adventure. I started to collect Adventure, then Bluebook, then Argosy. Rusty Hevelin finally got me to PulpCon, which was like walking into seventh heaven. I fell in love with the old pulps, and started to collect them – mostly the oddball titles – Zeppelin Stories, Yen Sin, all of that.

''My new non-fiction book, Science Fiction of the 20th Century, had a lot to cover. It's an enormous field. You can cover the paperbacks, the movies, the hardbacks, and the magazines, and think you've got it. You don't have it, not nearly. It's too damn diverse. Writing styles are too different, and what they cover is too different. In one respect, there's too many good authors! And there are little subgenres springing up all the time.

''It's very difficult for me to summarize all this in my book. The only way I could do it was in broad outline, and then anecdotally. Fortunately, in one respect, I'm one of the few writers in the field who did his apprenticeship at Ziff-Davis, did the longest professional interviews with Clarke, with Heinlein. I was just fortunate in being there, and being able to pick out little anecdotes that will illustrate things.

''Sturgeon was right: so much of the field is crap, it's alien invasions up the wazoo, the villains in the black hats, only now they've got tentacles, etc. But the very best science fiction urges the reader to speculate. Because of its nature, it appeals to a younger audience. That audience may not take it in book form anymore, but it certainly takes it in other forms. My hope would be that they would read more books, more paperbacks, etc., because that particular form of science fiction forces you to conjure up your own images of the future.''