|

Interview Thread

<< | >>

| MAY ISSUE |

-

-

Gibson Interview

-

-

-

-

May Issue Thread

<< | >>

-

Mailing Date:

29 April 2003

|

| LOCUS MAGAZINE |

Indexes to the Magazine:

|

| |

|

|

|

|

THE MAGAZINE OF THE SCIENCE FICTION & FANTASY FIELD

|  |

|

|

|

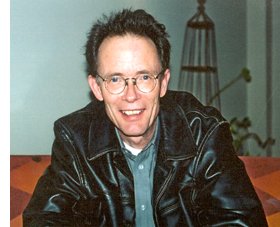

William Gibson: Crossing Borders |

May 2003 |

|

William Gibson was born in the US but left for Canada in 1968 to avoid being drafted into the Vietnam War. Early stories "Johnny Mnemonic" (1981), "New Rose Hotel" (1981), and "Burning Chrome" (1982) prefigured his seminal first novel, Neuromancer (1984) — winner of the Hugo, Nebula, Philip K. Dick, and other awards — which established the "cyberpunk" SF movement. Count Zero (1986) and Mona Lisa Overdrive (1988) followed, along with short story collection Burning Chrome (1986). Gibson changed gears, collaborating with Bruce Sterling for The Difference Engine (1990), a Victorian alternate history, and published Agrippa (A Book of the Dead), a poem about his childhood (text now readily available on the web). A near-future SF trilogy followed: Virtual Light (1993), Idoru (1986), and All Tomorrow's Parties (1999). His latest novel, Pattern Recognition (2003), is set in 2002. He lives in Vancouver with his wife and children.

|

Photo by Charles N. Brown

Official Website,

including blog

Directory: links to descriptions

and reviews of Pattern Recognition

|

Excerpts from the interview:

“I loved rocket ships, as a kid in the '50s: my dad's Oldsmobile had every space-motif in the book, I watched Tom Corbett, Space Cadet every night (Alfred Bester and Robert Sheckley each wrote some of those, I learned decades later), I carried my Willy Ley space-travel book around until the protective plastic wore off the cover, I played with toy robots. But by the time I started writing, in my mid-20s in the late '70s, it was the robots that had stuck with me, in the science-fictional part of my imagination. And not in the sense of 'mechanical men,' even in Isaac Asimov's more sophisticated interpretation, but in the sense of whatever 'thought-stuff' might motivate a machine: a sense of 'where do we stop and they begin?'”

*

“"The cyberpunk mode of Neuromancer and earlier stories grew quite directly out of a gut-level discontent with almost all of the SF of the late '70s and early '80s; 'decadent' was too rich a word for that stuff -- I despised most of it. I had become, in my quiet way, quite acutely pissed off at what the pop form I'd loved intensely in the '60s, and that had nurtured me powerfully and directly as an adolescent, had become. I still had a ragged shelf of Bester, Delany, Ballard, old New Worlds, and I was using Thomas Pynchon's Gravity's Rainbow as a bookend, all reminding me of what science fiction had meant to me. Talking about this, now, I reconnect with that sense of militancy -- and, hey, it's pretty refreshing! One powerful irony of this, I suppose, is that I always saw the 'cyberpunk revolution' as a roots movement, rather than as something new.”

*

“With Pattern Recognition, I made a deliberate decision to reset three basic parameters: 1) that it would take place in the summer of 2002; 2) that it would have a single narrative viewpoint (something I've never done before); and 3) that there would be relatively few ellipses in Cayce's narrative within the chapters.

“The previous three books seem to me to play with genre, and particularly to play a fairly complicated game with the conceit of 'the future.' If you look at my interviews over those three books, I think you'll find that I've been threatening to write a book like Pattern Recognition for a long time: a novel that makes what I've always been doing overt.”

*

“I don't think Pattern Recognition is SF, technically. It breaks a couple of my ground rules for science fiction. I won't accept as science fiction a story that involves inherently fantastic elements for which there is no attempt at rationale. Not that I can't enjoy a story of that sort -- quite the contrary -- but I don't think it's science fiction. Of course, you'll notice, here I am arguing that there is SF and not-SF, which I've already said isn't a distinction I'm particularly fond of. Make of that what you will. But there's no rationale, for instance, for Cayce's blatantly fantastic sensitivity to trademarks. And there's really no rationale for the ultimate source of the footage. These are two inherently fantastic elements that look more like 'fantastic realism' than SF, to me. I agree that the rest of it has the flavor of science fiction, but so does the world today. If I had been able to write a science fiction novel in 1975, depicting the world today exactly as it is, I'm not sure I could have gotten it published. It would have had too many scenarios running simultaneously -- AIDS, global warming, genetic manipulation, the collapse of the Soviet Union... Each of those is enough SF difference, in the traditional sense, for a novel. But in the real world, you don't have the luxury of changing just one thing.”

The full interview, with biographical profile, is published in the May 2003 issue of Locus Magazine.

You may purchase this issue for $7.95 by sending a check to Locus, PO Box 13305, Oakland CA 94661; or for $10 via credit card submitted by mail, e-mail, or phone at (510) 339-9198. (Or, Subscribe.)

|

|

|

|