|

Interview Thread

<< | >>

|

DECEMBER ISSUE |

-

-

Harrison Interview

-

-

-

-

December Issue Thread

<< | >>

-

Mailing Date:

25 November 2003

|

| LOCUS MAGAZINE |

Indexes to the Magazine:

|

| |

|

|

|

|

THE MAGAZINE OF THE SCIENCE FICTION & FANTASY FIELD

|  |

|

|

|

M. John Harrison: No Escape |

December 2003 |

M. John Harrison joined New Worlds in 1968 as editor and reviewer, participating in the New Wave movement centered on that influential UK magazine. His first novel, The Committed Men, appeared in 1971, as did The Pastel City, first in his well-known "Viriconium" fantasy series that continued with A Storm of Wings (1980), In Viriconium (1982), and numerous shorter works collected in Viriconium Nights (1984, 1985) and Viriconiuim (1988, expanded 2000).

Among his other novels are SF The Centauri Device (1974), literary SF Signs of Life (1997), and Light (2002), winner of the James Tiptree, Jr. Award. He's also written four contemporary cat fantasies as Gabriel King (collaborating with Jane Johnson), beginning with The Wild Road (1997), an

|

|

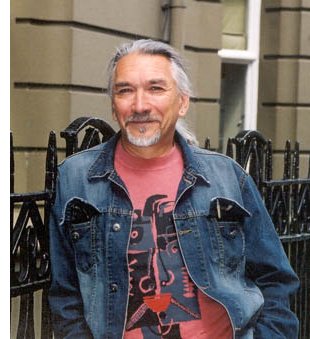

Photo by Charles N. Brown

Official Website

|

autobiographical novel on rock climbing, Climbers (1989), and several other short story collections, most recently Things That Never Happen (2002).

Harrison continues to review fiction and non-fiction for the Guardian, the Spectator, and the Times Literary Supplement, and teaches creative writing. He currently lives in West London with girlfriend Cath Phillips.

Excerpts from the interview:

“Writing is hard, but that’s the fun. Having been a rock climber for much of my life, I don’t have any problem with the idea that things should be hard. For me, constant challenge is the thing. Rock climbing is about pushing yourself. You’re always looking for the next level. Age is a limitation on a climber’s ability to do that, but a writer isn’t limited that way — at least until Dr. Alzheimer comes to call. You can continue to use your experience, and a very considerable stamina you get as you get older, to keep upping the ante. To do that you have to remain flexible. One of the last things you want is to be elected a Grand Old Guy. I would rather try to understand what somebody very young is trying to tell me about writing than take advantage of being able to pontificate.”

*

“So the ‘let there be light’ of Light was ‘OK, let’s have fun.’ Several decisions cascaded from that. One of the best ways to have fun is to try and ram different methods of writing together in the same text. I thought, ‘Do a horror novel, and a contemporary novel as well. Let’s see if space opera is elastic enough to absorb that.’ In the past, guys like William Hope Hodgson just wrote a weird book. They didn’t have to work with the rigid, formalized genre boundaries we have. These days, we wouldn’t know how to define what they did at Weird Tales, for instance: dark fantasy, or horror, or SF, or what? What I had with Light was a pure New Weird impulse before I’d even heard China Miéville use the word (this was about 1998-99).

“So the ‘let there be light’ of Light was ‘OK, let’s have fun.’ Several decisions cascaded from that. One of the best ways to have fun is to try and ram different methods of writing together in the same text. I thought, ‘Do a horror novel, and a contemporary novel as well. Let’s see if space opera is elastic enough to absorb that.’ In the past, guys like William Hope Hodgson just wrote a weird book. They didn’t have to work with the rigid, formalized genre boundaries we have. These days, we wouldn’t know how to define what they did at Weird Tales, for instance: dark fantasy, or horror, or SF, or what? What I had with Light was a pure New Weird impulse before I’d even heard China Miéville use the word (this was about 1998-99).

“I also asked myself, ‘Well, what haven’t I done for a very long time?’ The answer was out-and-out science fiction. And what is the absolute base level of science fiction? Space opera. I am from a generation that couldn’t avoid space opera - we loved it or hated it, or we loved it and hated it. I still think it is a fantastic medium. There’s nothing like big dumb objects and going very fast in space. The whole idea of alien artifacts was central. I reread some classic space opera, but I also read Alastair Reynolds’s first book, Revelation Space, and realized that one of the absolute driving factors of space opera is the discovery of alien artifacts. In the best space opera there’s this huge retrospective feeling: the aliens are already gone and you’re never really going to know what they were like, what they did, or how they viewed the universe. You’re left with their machinery and you don’t quite know what it does. One of the things I’ve got against old-fashioned space opera is how lisible, how easy, it made a vanished culture. For me the whole idea is that, when you come up against a civilization through its artifacts, you’re not going to know what 80% of those artifacts were originally for, either culturally or practically. For that concept, Algis Budrys’s Rogue Moon is an absolutely pivotal text, a favorite book of mine. Also, Arkady and Boris Strugatsky’s Roadside Picnic. If you’re going to look for influences on Light, books like that come very high on the list. I love the idea of living with technology you don’t quite understand, stuff that will inevitably change your own technology through hybridization. How you view a found technology, and what you choose to do with it, parallels exactly your relationship to primary scientific discovery: it will be controlled by the worst elements of humanity, and used for the most trivial and cannibalistic ends.”

*

“In the end you have to judge reality as the place where there are consequences. Anything else is willful and childish. Anything else is self-induced blindness, denial of the consequence of being alive, which is that you’ll die. You know you’re alive. My problem with cyberpunks is when they ask, ‘How do you know?’ Well, you put your hand down in front of a taxi. See how you feel with your hand under the wheel, see how well you use a keyboard afterwards; then tell me stuff about, ‘I don’t know whether it’s real or not.’ I don’t want to live in models, fictions, possibilities, alternate realities or multiverses: that’s for kiddies. I want to live and die as a human being in what is.”

“In the end you have to judge reality as the place where there are consequences. Anything else is willful and childish. Anything else is self-induced blindness, denial of the consequence of being alive, which is that you’ll die. You know you’re alive. My problem with cyberpunks is when they ask, ‘How do you know?’ Well, you put your hand down in front of a taxi. See how you feel with your hand under the wheel, see how well you use a keyboard afterwards; then tell me stuff about, ‘I don’t know whether it’s real or not.’ I don’t want to live in models, fictions, possibilities, alternate realities or multiverses: that’s for kiddies. I want to live and die as a human being in what is.”

The full interview, with biographical profile, is published in the

December 2003 issue of Locus Magazine.

You may purchase this issue for $7.95 by sending a check to Locus, PO Box 13305, Oakland CA 94661; or for $10 via credit card submitted by mail, e-mail, or phone at (510) 339-9198. (Or, Subscribe.)

|

|

|

|