|

Friday 11 June 2004

Letter from Brno

Spilberk fortress broods over the Brno skyline. Once the seat of Moravian margraves and Czech kings, this 13th century castle — rebuilt many times since — was transformed by the Hapsburgs into a prison (earning the nickname “The Dungeon of the Nations”) and perhaps was most famously used by the Nazi SS, who liquidated 80,000 lives in its miles of underground casements. Yet today, the white stone, red-roofed structure on the rocky oak-covered hill seems more like a monastery than a den of torture. Spilberk is a branch of the Brno museum, and the town below, sprawling outward for many kilometers (the second largest in the Czech Republic), is a charming architectural mix of the old, the truly ancient, and the strikingly modern. Advertisement From Brno’s cobblestone streets and sidewalks, the fortress is a landmark for the wandering tourist. I spend my mornings exploring, passing the storefront pizza parlors, the Lekarna pharmacies with their green crosses, the tony clothing boutiques, the internet cafes. WALK/DON’T WALK signs click like metronomes, hastening in double-time when the light turns green. Brno drivers have no patience for pedestrians, but the historic city center is a pedestrian-only zone; day and night, it bustles with couples, families, students, elderly men hopping on crutches. I may be the only one looking up. Like Prague, Brno has an abundance of Gothic and baroque decoration. Gargoyles glare down unexpectedly. Placid faces peer out from above the lintels of windows. In a looming bank façade, the pillars are carved giants. This is a city of ancient churches, like the 13th century St. Thomas, and the 15th century St. James the Grecian, with its splendorous baroque pulpit. Most impressive is the hilltop Cathedral of Saints Paul and Peter with its twin spires, rebuilt from the 11th century and said to mark the site of an ancient temple to Venus. Dolorous bells voice the hours. Farther out, near my hotel, Soviet-era tram cars sigh along their tracks, sparking at the intersections. At night, the sparks shudder across my ceiling.

# This is the town where Leos Janacek (1854-1928) spent most of his seventy-four years. In addition to the eccentric operas and chamber music he wrote here, he left his imprint in more concrete ways, founding a music school that thrives to this day, collecting and disseminating the folk songs of the near and far countryside, wresting a number of concert halls from Austrian hands to propagate a Czech — or more particularly, a Moravian — musical culture in his home town. Janacek (pronounced YAH-NAH-check) was a composer, ethnographer, naturalist, and amateur psychologist who wrote of all these concerns in vivid prose poems called feuilletons. This week he turns one-hundred-fifty. He’s partly to be found at the festival occupying the town’s two theaters — the historic Mahenova and the newer, uglier Janackova Theater — where all nine of his operas will be performed. But he’s also here among the Gothic scenery, on these lion-colored cobblestones.

# Soon after my arrival, I ventured out in search of his house. I had left behind the snows of Prague and the snowy beech and pine of the Czech countryside. In clear, sunny Brno, the air was painfully cold those first few days. Armed with my hotel map, I soon found the Italianesque façade of his original music school, now home to an important archive. Beside it, tucked into a clearing between the school and the building next door, was the small cottage the school built for him, in what had once been a horse pasture.

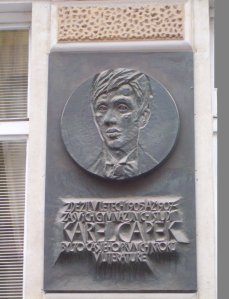

Now a museum, its cramped interior is fitted with multimedia and display rooms. The Maestro’s study is presented as it might have looked during his life. A piano dominates the space, surrounded by rustic furniture. In a glass case stands the mysterious Hipps Chronoscope, which he used to precisely measure human speech. I was especially captivated by the displays — the handwritten scores to his major works, the memos, old photographs, and, in one of the glass-fronted cases, a letter from the great Czech SF writer Karel Capek. Unknown to me then, I would soon hold even more precious items in my hands. # On one of my walks, when Spilberk is lost behind gargoyle-studded facades, I spy a bronze plaque above the sidewalk. Capek (1890-1938) had lived near Prague. I wasn’t aware that he’d spent any length of time in Brno, though he might have seen the local premiere of his play R.U.R., whose music had been provided by Janacek’s greatest student, Pavel Haas. And he certainly visited for the premiere of Vec Makropulos (The Makropulos Secret) in 1925. Last night, I attended a performance of the opera in that same theater, the Mahenova. My seat was ideal: sixth row center. It was, I like to think, the seat Janacek might have tried to provide Capek. The author had given only grudging consent for the composer to adapt his play, and apparently forgot the project until notification of its Prague premiere. The performance in Brno appeared to overwhelm him. Afterward, according to his sister’s memoirs, he was “positively glowing, drinking mutual toasts to the Maestro.” Last night, moments before the overture began, I spotted a pale cameo ensign of a black, two-headed eagle high above the stage. Here in Brno, in unexpected places, the Hapsburgs linger. # Through most of Janacek’s life, Brno was a German-speaking town known as Brunn. The composer was always a troublemaker when it came to the occupying powers. He refused to speak German to his wife’s German parents or to ride the German streetcars. He feared that Czech language and culture were in danger of dying out completely under the double-monarchy. On a professional level, the reigning prejudice inhibited his attempts to get his operas performed and reviewed. Even after his opera Her Foster Daughter was successfully staged in Prague, he found it difficult to penetrate into Vienna and reach the wider world, until Max Brod — who was also Kafka’s champion — translated the libretto into German. Arguably, he wasn’t the town’s most famous resident. Johann Gregory Mendel (1822-1884), the botanist and the father of Genetics, carried out his experiments with peas and bees in the Augustinian monastery on Solnicni street. Erich Wolfgang Korngold (1897-1957), the Hollywood composer, left for Vienna at a young age; his prodigious success saved him from the fate of most of the town’s Jewish population, including Janacek’s student, Pavel Haas. # Soon after snapping the photo of the Capek plaque, wandering the lion-colored cobblestones, I come upon the Arakis SF and Fantasy bookstore. Brno is well-represented by bookstores. Two very fine establishments are located in the historic city center — multi-floored, well stocked not only with Czech literature but exemplary music sections, and a good selection of English-language books. Still, it’s surprising to find two S.F. bookstores as well, within walking distance of one another. Like the other — Cerna Planeta — Arakis has a familiar interior of wooden shelves, garish pulp covers and comic book-laden tables. Less familiar is the incense-tinged air. I approach the bearded, Rasputin-like owner and ask about Capek and the plaque. I show him the image in my digital camera. Supposing my Czech is more advanced than it is, he launches into an explanation lost to me. I nod throughout, then ask some simple questions, and deduce that Capek lived here in his youth. Only later will I get the plaque translated: “Here lived in the years 1905-1907/during his high school studies/Karel Capek/It was the time of his first steps/in literature.” I begin to peruse Arakis’s inventory, which includes many Frank Herbert and Orson Scott Card translations. I’m searching (in vain) for Svatopluk Cech’s The True Excursion of Mister Broucek to the Moon, the basis for Janacek’s third opera, due to be performed in a few days. Those other excellent bookstores have already sold out their copies. # The Excursions of Mister Broucek (1918) is — at least for me — the festival’s high point. An extravagant production of scrims and projections, full of beery humor and sleight-of-hand theatrics, it arrives directly from a hit run at Prague’s National Theater. The conductor is Sir Charles Mackerras, the greatest interpreter of Janacek; another famous conductor, Sir John Eliot Gardner, is in the audience. I have a front row seat to the left of Mackerras. I can glance down at the orchestra, right at the conductor, up and ahead at singers. The performance — orchestrally, vocally, dramatically — is a triumph, and even manages to make the second Excursion into the Fourteenth Century seem persuasive. As the work comes into the home stretch, I realize that I’ll probably never again witness such a rendition of a Janacek opera, certainly not living in Seattle. There’s no doubt about it: I’m giving this a standing ovation. And it’s soon apparent that I’m the only one. Though warmly clapping, the audience remains seated. Brno doesn’t seem to go in for standing ovations; maybe it’s a lingering mindset from the Communist era, or maybe, in the case of this Broucek, there’s an unwillingness to display such gratitude to out-of-town Praguers. Maybe I’m totally off-base in my love of this production. Who cares. I remain standing and clapping, even as two elderly ladies behind me begin grousing in guttural German. I ignore them — after all, I’ve traveled halfway around the world to attend this festival, I’m going to stand and clap. The grousing grows louder. One reaches forward and begins tugging at my suit jacket, trying to pull me into my seat. Fucking Germans. # I admit it now. As I wander the cobblestone sidewalks, I’m looking as much for Pavel Haas as for Janacek. Haas (1899-1944) was not only the Maestro’s greatest student, but a disciple of his unique style of composition, inspired by folk song and the rhythms of natural speech, as well as a sense of modernism not detached from human emotions and experience. He was never able to write full-time. For many years, after his required stint in the Austrian army, he worked as a partner in his father’s shoe shop. In 1935 he married Sona Jakobsonova, a doctor. They had a child named Olga. Haas’s style changed as he matured, embracing Parisian jazz in his string quartets, and Hebraic modalities in his unfinished Symphony of 1941; his Jewish faith, toward the end, would come to the fore. He wrote much for the theater, and many Czech film scores (his brother Hugo was a famous actor who later emigrated to Hollywood). His only opera, Charlatan (1938), for which he wrote the libretto, approaches Janacek’s mastery. My first day in Prague I journeyed north to Terezin, another Austro-Hungarian fortress. Known also as Thereisenstadt, it became Hitler’s “model” concentration camp, where the outside world was shown the pleasant life the Jews had in their new ghettos. Haas was one of nearly 10,000 Brno residents sent there between 1939 and 1945. In the Terezin museum, I discovered a small display of his manuscripts, along with the work of other composers who ended up behind its garrison walls — such as Viktor Ullmann and Gideon Klein. Today, in Brno, few seem to know much about him. A biography, published in 1995, isn’t stocked by either of the excellent bookstores. Only when I ask at Janacek’s house do I receive help. The woman at the counter suggests with disarming simplicity that I go next door to the Janacek Archives, which possesses most of Haas’s original manuscripts. Giddy at the thought — I’m no scholar, have no credentials — I leave the house, walk slowly past the locked and silent side-door to the historic School, stop on the cobblestones beyond the gate, ponder, then return to the door and ring the bell. # Luckily, the gatekeeper speaks English. I’m a writer researching Pavel Haas, I tell her. I mention the trio of interconnected novellas I’m working on, inspired by Capek’s Trilogy, the first dealing with Janacek, the second with Haas, and the third with Capek himself. To my surprise, I’m ushered in. The archive’s reading room is reached at the end of two hallways, a comfortable clutter sided with a massive card catalog and bound journals. A large table takes up most of the floor space. A few American scholars and musicians are at work, very affable, whispering welcomes to a newcomer, answering my naïve questions. John Tyrell, the dean of Janacek scholars — and Executive Editor of the Grove Encyclopedia of Music — is seated by the window, at work on his imminent, anticipated biography of the composer. Only slightly intimidated, I flip through the yellowed cards in the catalog, surprised by the number of original Haas manuscripts in their collection (and not yet daring to look for Janacek’s). I fill out the request forms for Charlatan and the unfinished Symphony. Regrettably, his score to Capek’s R.U.R. is absent from the otherwise extensive list. I hand the form to the librarian. Promptly, the works are retrieved from the inner sanctum and laid before me on the table: Charlatan, in three oblong bound books decorated with Haas’s own drawings; and the unfinished 1941 Symphony, a work written as the Nazis were rolling into town. Notated in pencil and pen on tall, folded octavo sheets, the neatness of those first movements contrasts with the sketches collected in the back — fierce scrawls and scratch-outs and erasures of a desperate creative mind. I caution myself to lift and turn the pages slowly. Should I be wearing gloves? Carefully, I turn back to the first page and read the staves. My rudimentary skills are aided by a vivid memory of the orchestral performance. In the hush of the reading room, I’m hearing those first two notes played by the strings and woodwinds, an anguished interval suggestive of a synagogue hymn, from which the rest of the impassioned argument is formed. Even when I can no longer follow it, the written music — so precisely and carefully laid down in pencil and pen — holds my eyes. I wonder whether Haas had worked in this very room when he attended Janacek’s school. I sense him at my shoulder. In later days I request some of the Maestro’s own works, such as the first drafts of his beautiful chamber piece Fairy Tale, and the operas Jenufa, The Excursions of Mister Broucek, Osud and The Adventures of the Vixen Bystrouska — these last two not the originals but venerable copies made on thick, silvery paper, perhaps of Soviet design, with Janacek’s fierce, thickly-inked notation slightly blurred across a surface that has a texture like vellum. Most beguiling to this sometime-science fiction writer is Janacek’s copy of Capek’s Vec Makropulos, the margins of the book filled with eccentric annotations, cross-outs and culls, snippets of music (the first of many cellular motifs he would propagate in his early drafts only to weed and thin into the final product) as well as weird graphical symbols whose meaning evades even the scholars around me. Leos (one whispers) sometimes scribbled the strangest things. # Spilberk fortress, for Janacek, became a benign presence at the end of World War One, with the beginning of Czech independence. “One day I saw a miraculous change in the town,” he writes, “my hatred of the Spilberk jail, inside whose depths so much misery had been suffered, disappeared. Over the town the light of freedom blazed, the rebirth of Oct. 28, 1918!” For a time, he lived in a house with a view of Spilberk out the living room window. Later, in his school-side cottage, he enjoyed walking to the parkland along the hill. In one of his feuilletons he contemplates the voice of a housekeeper calling for her hens on the hillside, notating the speech melody of her “Here, chick chick chick, here here here.” His life, it might be said, was framed by history for optimum effect. His most productive years, from 1918 to his death in 1928, were lit by that light of freedom, giving us his masterworks Katy’a Kabanova, The Adventures of the Vixen Sharpears, the Makropulos Secret, From the House of the Dead, the Glagolithic Mass, the Sinfonietta, the Concertino, the Cappricio, and the two string quartets. Pavel Haas, on the other hand, was blindsided by history. I contemplate this late one afternoon as I climb Spilberk Hill. The idea for the walk was impulsive, and probably misjudged. It had snowed in Brno the night before. All but one of the sloping paths leading up the hill is lost in ice. Yet the air seems bearably warm, so I start up the plowed path for my first and only visit, pausing to snap a photo of the dramatic trees. When I arrive at the top, and the fortress’s red-roofed structures are revealed, the few people in sight are headed down the hill. It’s after five p.m., I realize; the museum rooms are now closed. I wander the battlements, coming upon a lone statue of some ancient benefactor. Nearby is a gnomic temple with a view of the town slipping into dusk. From here, Brno’s charming mix of modern and ancient is muted. The church spires are murky in a wintry haze. At some point, unnoticed by me, the nearby lamps have lighted. Darkness has settled over the hill. The cold is penetrating my shoes and gloves and coat. I approach a strange basin and its grinning face. And a guard tower. I peer out its oblong window. Seemingly alone, I walk under a castle arch into a lighted courtyard. I find an information kiosk. With a touch of the button, a recorded voice tells of Spilberk and the underground casements, which are surely closed at this hour. The kiosk remains talking as I wander farther in, along another arching hall where the doors to the museum stand locked. The interior courtyard is medieval. At the far end, under a strange branch of bells, a baroque crown of black-iron caps what looks like a well. A nearby placard names it the deepest well in all of Moravia. Leaning over, I can feel a draft of air even colder than the hillside. These twists of cold metal under my hands, this subterranean air, reminds me somehow of Haas’s unfinished Symphony. A similar sense of dark currents, remote yet tactile. Leaning over, I almost expect to hear faint silvery echoes of violins, cellos, woodwinds. I almost taste them on my tongue. Haas himself was not sent to Spilberk. Instead, he received a slip of paper under his door notifying him to report to Gestapo headquarters at a local school. Along with hundreds of his fellow townsfolk, he was taken by darkened cable car to the train station, and transported to Thereisenstadt. It was there, in 1944, that fate conspired to make him a central player in Hitler’s charade. To show the Jews were prospering in their Ghetto, the Nazis staged a classical music concert and filmed it for posterity. The featured work was Haas’s Study for String Orchestra, one of a half-dozen pieces he wrote at the camp. The players were lent black suits. The conductor Karel Ancerl (who would survive) later recalled how potted flowers were arranged to hide his clogs. The filmed performance was — still is — intense. The Study is fierce, pained, inspired by Stravinsky’s motoric rhythms, yet somehow hopeful, even as it lacerates the listener’s ears. At the end, Haas, looking haggard, can be seen accepting the applause of his audience of prisoners. Days later, he would be sent to Auschwitz on the last train to leave the camp, and be executed upon arrival, at the age of 44. The snow on the hillside glows a soft blue, under what seem Victorian gas-lamps. Trying to locate the plowed path, I find only the ice-covered ones. Spilberk looms to my right, and whatever ghosts haunt the hill are surely active. To my left, beyond the stark trees, the lights of Brno are sparkling, welcoming, cheerful. With only a few missteps, I find my way back to them.

David Herter is the author of Ceres Storm and Evening’s Empire, both from Tor. He is hard at work completing In the Photon Forests and Yan Tan Tethera, the first half of a far future quartet, forthcoming from publishers unknown. |

|||||||||

| TOP |

|

© 2004 by Locus Publications. All rights reserved. |

Subscribe to Locus Magazine |

E-mail Locus |

Privacy |

Advertise |