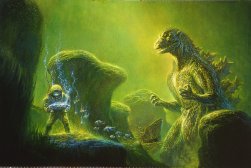

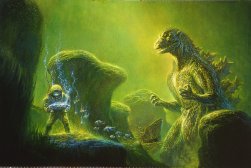

Painting copyright 2004 Bob Eggleton, Godzilla TM& (C) Toho Co. Ltd 1954,2004. Click for larger image.

On November 3rd, 2004, Godzilla — the giant Japanese monster and pop culture icon — became exactly 50 years of age. In November 1954, Toho Studios released Gojira to theaters in Japan: the first film of its kind for that country. Toho producer Tomoyuki Tanaka was inspired to create Gojira after hearing the disturbing story of the fishing boat Lucky Dragon No. 5 that had been an unwitting witness to a US atomic test someplace in the Pacific. The crew of the Lucky Dragon No. 5 recalled being covered with an ash that came down like snow, and upon return to Japan they succumbed to severe radiation sickness. Unfortunately, some of their tuna catch made it into public markets and it was discovered, too late, that the tainted fish had been consumed by Japanese residents. The tragic story caused an uproar in Japan, forcing many to confront the frightening side-effects of the seemingly obsessive and pointless A-bomb testing by the US, not to mention the insidious after-effects of the bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

And so Gojira, inspired both by the fishing boat incident and by The Beast From 20,000 Fathoms, a film released a year earlier, was born. Producer Tanaka brought aboard Kurosawa-protégé Ishiro Honda as director, and special effects wizard Eiji Tsuburaya, for what would be Toho's most ambitious film to date. Tsuburaya was deeply in awe of Ray Harryhausen's (then) state-of-the-art stop-motion effects, but could not afford the cost and time involved. Instead he created the technique of "Suitmation", along with some puppet work here and there, to depict the "Gojira" monster. The name "Gojira" comes from the Japanese words for "Gorilla" (Gorira) and "Whale" (Kujira), thus "Gorilla Whale". Godzilla is not just a mutated dinosaur, but also a "Kaiju" — a Japanese word meaning some kind of mythical monster. Godzilla, in this case, was roused from hibernation and mutated by the testing of H-bombs.

Unlike other giant monsters, Godzilla has radioactive breath (making him a true Weapon of Mass Destruction), lending the film a pervasive sense of doom and dread. The Akira Ifukube score is moody, somber and unlike any other music for a film of this type — it sticks in your mind long after the film has ended. The face of Godzilla is like gazing into the face of death. In the film, a strong subplot parallels the giant mutated monster story: Dr Serizawa, himself a physically maimed war hero, accidentally discovers a deadly weapon while experimenting with properties of oxygen. Named the Oxygen Destroyer, it "disintegrates" oxygen in water and thus, destroys the life contained in it. So scared that his unwitting invention will fall into the hands of "the devils" (referring to politicians and the military) he keeps it secret until the need to use it on Godzilla becomes inevitable. But the disturbed scientist makes the ultimate sacrifice and kills himself along with Godzilla, so his secret dies with him. In his own words, he reasons: "A-Bomb vs. A-Bomb, H-Bomb, vs. H-Bomb... where does it stop?" He cannot bear the responsibility of having the secret of such a potentially evil device made known to the world.

The film was a major box office hit in Japan because it touched upon the public's fear of nuclear devastation, and contained the elements of something uniquely Japanese: a complete and total respect and awe of nature itself, a sense that Mankind is simply a cog in the wheel of the great machine known as planet Earth.

In the US, the film was screened for Japanese residents at the Los Angeles Toho LaBrea Theater, and in the audience was producer Joesph E. Levine, who subsequently bought the film for US release for his company Transworld Pictures. The film became Godzilla, King of the Monsters (1956).

Levine's release, however, was a truncated version of the Japanese masterpiece. The US version's reputation for being "cheesy", though in part due to the primitive (by today's standards) special effects (and one could apply the same charge to Harryhausen films of the same era), is largely due to the re-editing that obscured the original's powerful and stark message of nuclear nightmare and the long-term results of tampering with nature. The US version, edited by Terry Morse, was poorly dubbed and featured an awkwardly inserted Raymond Burr as a US newspaper reporter, in a totally re-framed film. The original Japanese version is a dark, and in the end tragic, film that provided a glimpse into Japanese social and family ideals: sacrifice for the greater good, and honor. The US edit diminished these themes, and vastly trimmed down the "Anti-nuke" tone for a 1950's Cold War "pro-nuclear" America. After all, there were days when no one wanted to release a film that had anything questionable to say about US policies.

In 2004, Rialto Pictures released the original 1954 film Godzilla, thankfully sans Raymond Burr and the Terry Morse footage, to art-house theaters in the US on a staggered release. It's received rave reviews, and is certainly worth seeing if you can catch it. The 50-year-old film has succeeded beyond Rialto and Toho's wildest expectations: in May it set a per-theater sales record at two theaters in New York City, beating out Van Helsing, released the same day.

Even though Godzilla "died" in the first film, Toho knew they had a good thing and conveniently found another Godzilla of the "same species" for a sequel, Godzilla Raids Again (1955), which found its way to US shores under the confusing title Gigantis The Fire Monster (1959) in a ghastly re-edit that made it almost un-watchable. This sequel was kind of slapped together anyway, by comparison to the original, and not directed by Ishiro Honda. It introduced a new monster for Godzilla to battle — Anguirus — so as to suggest that man's nuclear experiments could free further hordes of monsters. The film was rushed out a mere six months after the original film. Toho went on to more science fictional entries such as The Mysterians (1956) and Battle in Outer Space (1959), both highly imaginative technical tour-de-force alien invasion epics. The studios even made an excellent horror film called Matango (1963), based on William Hope Hodgson's story "The Voice in the Night", but released in the US as the strangely titled Attack of the Mushroom People. They also did two "giant Frankenstein" films — Frankenstein Conquers the World (1965) and War of the Gargantuas (1966) — as they explored still other Kaiju variations.

*

Godzilla took a seven-year hiatus, returning in King Kong Vs. Godzilla (1962) which had its origins in a Willis O'Brien treatment submitted to Universal Pictures as King Kong Vs Prometheus (as in Frankenstein, a long story in itself). King Kong Vs. Godzilla starts off with Godzilla destroying a US sub, and the film quickly becomes a battle of "East vs. West" with Kong representing the West. Superficially a monster tag-team match, the film's message addresses the clash of cultures and commercial crassness with, at one point, Kong being "sponsored" by a pharmaceutical company "tired of all the attention on Godzilla". An outright satire, it must have struck a chord: it remains the top grossing Godzilla movie in Japan to this day. The US version of King Kong Vs. Godzilla was also re-framed and vastly edited by Universal, who excised the excellent Ifukube score and inserted some patronizing "United Nations" scenes with awful actors.

By the 1960s, Toho had entered their "Kaiju Eiga" phase in which the films were shot with a dream-like, modern fairy tale look, in stunning color and wide-screen "Tohoscope". They'd also created a menagerie of giant monsters — Varan, Rodan and Mothra — all starring in their own films. Godzilla returned in Mothra Vs Godzilla (US title: Godzilla Vs The Thing) in 1964 to battle the monster moth. This film also had an anti-nuke message, suggesting (though not spelling it out) that Mothra was also created by radiation, as her home Infant Island was laid mostly to waste from heavy water experiments. This film had a terrific subplot that concerned itself with the social comment that greed and again, commercialism, are too often favored at the cost of life and nature itself: two unscrupulous characters fighting over an overcoat full of money, while Godzilla destroys the building they are in, vividly illustrates the theme. Many fans consider this the best of the '60s sequels, defining Godzilla as a natural force and a destroyer of life. The film also featured a scene made solely for the US: a segment with US ships bombarding Godzilla with missiles. The image of US flagged ships hitting Japanese soil with weapons would not have played well with Japanese audiences of the time, and their vivid recent memories of war, so this scene was missing in the Japanese version.

Later in 1964 Godzilla became the friend of mankind, battling a space-born dragon in Ghidorah The Three Headed Monster(1964), but alongside Mothra and Rodan to protect home turf. The growing children's audience for the monster's films is suspected as the reason for softening Godzilla's image to one more "friendly".

The tri-headed dragon, King Ghidorah, returned in Monster Zero (1965) to battle Godzilla and Rodan on another planet in a space opera story that remains one of the best examples of the '60s sequels. This film combined the elements of what was working for Toho at the time: Kaiju Eiga and space operas. It also starred the late Nick Adams and was made as an American co-production, though it wasn't released in the US until 1970, two years after Adam's death.

The film has a pace like no other in the series and it contained several "firsts". For the first time the monsters took a backseat to the human characters and story. Nick Adams was the first major Western actor to actually star (as in, perform on set) in a Toho Kaiju film and his presence gave international audiences a face to recognize. His chemistry with the other actors was legendary. Another first: Adams' character had a relationship with one of the Japanese female characters — a taboo at the time in Japan to depict onscreen. By this time, other than in one reference, Godzilla's radioactive metaphors were forgotten in favor of the monster being a savior to Mankind from outside and alien threats. The "East vs. West" symbolism was moot, with an American astronaut appearing in the plot as part of a joint space mission. It seemed that we were all in this together, including Godzilla and friends, to face threats that would come from beyond our world.

After this point, Ishiro Honda left the series and handed the reigns over to Jun Fukuda who, in 1966, directed Ebirah Horror from the Deep (US title: Godzilla Vs The Sea Monster). The name Ebirah comes from "Ebi" — a giant shrimp. In the next film, Godzilla had a "son" Minilla (a.k.a. Minya) in the aptly titled Son of Godzilla (1967). These were two of the most unusual sequels in the Godzilla series, as they reflected both the popularity of James Bond films and surfboard movies, and the color palette and music of the Groovin' Sixties. By this time, Godzilla was playing to "date" crowd audiences and children. He was changin' with the times.

Yet, box office for the films dwindled, and 1968 saw what Toho purported to be the last of the series: Destroy All Monsters, which featured most of the Toho monster menagerie in a futuristic alien invasion tale. It was a spectacular entry, with Honda returning to direct. Despite its intent as Godzilla's "swan song", it did well enough that the next year, Honda directed All Monsters Attack (1969) (US Title: Godzilla's Revenge), a film made up mostly of "clips". It was a great use of footage from past battles strung together more or less as a daydream for a young boy being bullied at school who got his courage from Godzilla & friends. This was sheer kids' fare as a film, with very little new monster footage filmed, due in part to Eiji Tsuburaya's ill health and death in early 1970.

As the 1970s dawned, and worries of pollution became more apparent in Japan, maverick director Yoshimitsu Banno helmed Godzilla Vs Hedorah (1971) (US title: Godzilla Vs The Smog Monster) — which remains to this day, the closest Godzilla ever got to being in an "art" film. Here we have the irony of a monster born of radiation, vanquishing a monster made of industrial pollution. The film has a quirky pace, featuring a young boy who owns Godzilla toys and sees him as a protector, and had anime segments and acid rock music.

This was an age of "anything goes", and Godzilla was forced to compete with television and superheroes, so Toho reached deep into the creative well with two unusual entries. First, Godzilla Vs Gigan (1972) had a story involving a comics/manga creator, cockroach aliens, a cyborg monster Gigan, and, a talking Godzilla. Godzilla Vs Megalon (1973), was a superhero-type film, portraying a giant robot teaming up with Godzilla to battle a bug monster from the earth's mantle. Then, Godzilla Vs Mechagodzilla (1974) dumped the childish plots of the previous two films with a Yakuza-like film plot (and violence), having Godzilla team with a giant Okinawan "Foo-Dog" monster, King Seesar, and battling a mechanical alter ego, Mechagodzilla, controlled by aliens. All three films were helmed again by director Jun Fukuda, and each one did unspectacular box office. The film industry in Japan was in dire straits, in the '70s, with US imports dominating the box office, hurting Godzilla's performance deeply. Still, Toho brought back director Honda and tried once more in 1975 with Mechagodzilla's Revenge (US title: The Terror of Mechagodzilla). The film was a noble attempt at re-capturing the "golden days" of the previous 10 years, and, to a point, it worked. Perhaps the best of the '70s Godzilla entries, it was nevertheless a failure at the box office, and it seemed time for Godzilla to finally retire, after 21 years of stomping success.

In the 1980s, after a successful repertory showing of some of the '60s Godzilla titles, producer Tanaka and Toho decided that a return of the giant monster was in order. However, they disregarded everything made from 1955 to 1975, and used only the 1954 film as a basis for Godzilla (1984) (US title: Godzilla 1985), a film which made the monster an enemy of mankind and re-introduced the anti-nuclear theme of the original movie. The film also played with some US/Soviet politics of the Reagan era, appearing to make the US the deceitful aggressors with their causing the "accidental" detonation of a Russian nuclear bomb. The US version — which again had Raymond Burr (and Dr Pepper as a product placement) badly inserted into the middle of the film — re-edited the politics to make the Soviets appear to be the bad guys. The film played well enough to warrant a sequel in 1989, Godzilla Vs Biollante — based on a story by the winner of a contest! Again, a serious tone was taken, making Godzilla a dangerous mutation and battling a giant mutated rose bush. Again, the film featured an untrustworthy "American corporation" cooperating with Middle-Eastern terrorists from the mythical land of "Saradia". Box office was less than expected, so Toho brought back more familiar monsters in Godzilla Vs King Ghidorah (1991) — a film which explored some convoluted time-travel science, questioned the consequences of Japan's economic power, and gained some controversy due to the inclusion of a pre-mutated Godzillasaurus wiping out some US soldiers and thus protecting a Japanese garrison on a Pacific island in WW2 — the war as seen from a Japanese point of view. This was followed by Godzilla Vs Mothra (1992), and Godzilla Vs Mechagodzilla 2 (1993), which re-imagined battles from the past films.

Then in 1993, Sony/Tristar signed a deal to make a US Godzilla film. At first announced to be directed by Jan DuBont, from a script by Terry Elliot and Ted Russo, it had a story that had the flavor of the earlier Japanese counterparts. Sony balked at DuBont's required budget of $130 million, and the project went into turnaround. Toho however, decided it was time to do two more Godzilla films — Godzilla Vs Space Godzilla (1994), and Godzilla Vs Destroyer (1995), in which an ailing Tomoyuki Tanaka (who died later that year) announced an end to the monster by killing him.

*

In 1996, fresh from their success with Independence Day, the team of Roland Emmerich and Dean Devlin signed with Sony to make a big budget US Godzilla. Their treatment, despite an enormous budget that led to nightmares, "re-imagined" the creature so far from its base idea, that the film missed the mark with hardcore fans in both the US and Japan. The appearance of the creature was altered to the point of only vague resemblance to the original, and his origin became that of a mutated marine iguana, not a dinosaur. Emmerich and Devlin even got rid of his atomic breath, calculating (wrongly) that audiences would see that aspect as "unrealistic". Their monster was cool looking, but it wasn't "Godzilla", and being almost completely CGI, the film was more Jurassic Park than a "Kaiju" film. Worse, Emmerich and Devlin failed to define the monster as either Good or Evil, and they made it something of a frightened kitten, running from the military and, worst of all, easily killed. All this on top of a goofy human drama that was mostly forgettable.

The film lacked the quality that made the Japanese Godzilla films, at the very least, entertaining: they allowed the audience to insert some of its own imagination. Sure Godzilla looks totally incredible and unbelievable... but just go with it. The different approach reflects a basic difference between US and Japanese film goers. It's the same reason a Hayao Miyazaki animated film can make $300 million in Japan, get critical raves and all kinds of awards, yet barely get a release Stateside. Western audiences (as a generalization) find films with any kind of mythological basis difficult because they don't know what to make of them. Perhaps the trend of explaining absolutely everything in Western films has left that audience with atrophied imaginations. In Japan, audience participation, in the use of their imagination, is essential. The Saturday morning Godzilla spin-off cartoon (made by Sony animation) was more of a hit with fans because while it used the same creature seen in the film (and essentially the same human characters) it used imaginative scenarios and had other monsters to deal with. And, Godzilla got his atomic breath back. Perhaps if this approach had been taken with the film, it would have been a more profitable and memorable event.

In 1999, Shogo Tomiyama, a Toho producer, stepped into the shoes of the late Tanaka and announced that Toho would create a "new Godzilla". Again using only the 1954 Godzilla as a starting point, there would be three totally "unrelated" Godzilla movies helmed by three different directors. The first was Godzilla 1999 Millenium (US title: Godzilla 2000) in which he battled the inhabitants of a eons-old spaceship; then Godzilla Vs Megaguirus (2000) was a kind of alternate history Godzilla tale. Finally came Godzilla, Mothra, King Ghidorah: Giant Monsters All Out Attack (2001), which is considered the stand-out in the series of recent films due to director Shusuke Kaneko's involvement in all aspects of the production. This film was actually quite on the mark, with Godzilla having somewhat mythic origins, and functioning as a metaphor for war and death. Kaneko brought Godzilla back to his 1954 persona of being an evil monster. He envisioned the creature as inhabited by the souls of "all the war dead — from WW2" and had Godzilla battle the "Guardians of Yamato" (based on an actual Japanese legend) — Ghidorah, Mothra and Baragon — Toho Kaiju, but once again, all in re-imagined roles.

After that came the more lighthearted and science-fictional Godzilla X Mechagodzilla (2002) (US title-Godzilla Against Mechagodzilla, which features yours truly as a fleeing extra) and Godzilla X Mothra X Mechagodzilla-Tokyo S.O.S. (2003): a pair of films that had a great story arc, and plenty of action, but again ignored all that came before save for the 1954 film. These films (both directed by Maasaki Tezuka) saw Godzilla as part of the biosphere of earth and, due to Mankind's tampering with DNA — the creation of a "MechaGodzilla" from DNA from bones of the 1954 Godzilla — resulted in the monster attacking Japan. In these two films, the MechaGodzilla was named "Kiryu" (Japanese for "mechanical dragon") and the plot explored the ethics of DNA experimentation and whether it is moral to create a life form to be used solely as a weapon.

*

Toho's FX have vastly improved (especially in the recent films), but while CGI is used in places, they have avoided Hollywood's virtual fixation on it and instead continue to rely on "man in a suit" stunt actors. Toho's thinking is that CGI is expensive and, no matter how good looking, it lacks the volume and "reality" that an actor in a suit (combined with model work) convey. This is a viewpoint most Godzilla fans happily share, despite the resultant reputation of the series as low-budget late night cable fodder. More importantly, over the course of 27 films, Godzilla has changed vastly and subtly in appearance and demeanor. He has evolved constantly, reflecting changing tastes and attitudes over five decades. If he had not, his popularity probably would not have lasted more than a few short years. I think this is a good way to view Godzilla and his success.

Now, in 2004, Godzilla celebrates his 50th anniversary. About to be unleashed is the 28th Godzilla installment, Godzilla: Final Wars, which appears to have a record cast of fourteen monsters, and a lot of publicity. The film will even feature an appearance by the American Godzilla! Once again, Godzilla is wholly re-imagined from 1954 by energetic director Ryu Kitamura, though the story is shrouded in secrecy. The film will debut not in Japan, but in Los Angeles at Grauman's Chinese Theater on Nov 29th, the same day that Godzilla receives his star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame — truly a feat for a fictitious monster. Despite the series' low-budget reputation, no one can deny that Godzilla's popularity over the past 50 years has earned him a place in the Science Fiction and Pop Culture universe like no other.

Notes: English titles of the films are cited here, as many of the films have several titles, and long ones at that, particularly the early ones, in their original Japanese. For the ease of the reader I opted for the titles probably known best. Sony/Tristar has recently released affordable, gorgeous widescreen prints on DVD of some of the older films and, the newer series, and you can enjoy them subtitled or dubbed. They're worth seeing if you've only seen older versions, which were usually presented in poor formats, panned and scanned prints, usually from 16mm copies and, badly dubbed in some cases.