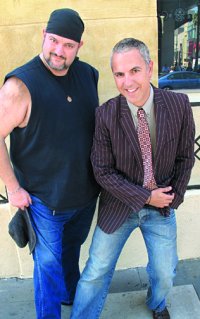

Dani & Eytan Kollin: Desperation and Inspiration

Dani Kollin was born June 25, 1964 – ‘‘George Orwell’s birthday’’ – on an Air Force base in Ankara, Turkey, where his father was stationed. He moved to the States when he was three weeks old. He attended UCLA, graduating with a degree in graphic design and communications, and later worked as a graphic designer and eventually as a copywriter.

Dani Kollin was born June 25, 1964 – ‘‘George Orwell’s birthday’’ – on an Air Force base in Ankara, Turkey, where his father was stationed. He moved to the States when he was three weeks old. He attended UCLA, graduating with a degree in graphic design and communications, and later worked as a graphic designer and eventually as a copywriter.

His brother Eytan Kollin was born February 2, 1967 – ‘‘Ayn Rand’s birthday’’ – in Spokane WA. He got a BA in 1991 and a teaching credential for history in 1999, and has taught high school.

The family moved frequently, and they grew up in Washington State, Florida, Michigan, New Jersey, and California.

Their debut novel, The Unincorporated Man (2009) won the 2010 Prometheus Award for best science fiction novel of the year from the Libertarian Futurist Society. Sequel The Unincorporated War appeared in 2010, and third volume The Unincorporated Woman is forthcoming in August 2011. A fourth volume is expected to conclude the series.

Dani has been happily married to the same woman for 20 years, and has twin 10-year old boys and a 13-year-old daughter. He’s an avid endurance cyclist and surfer. Eytan is single and his hobbies include melee weapons and knitting.

Website: The Unincorporated Man

Dani Kollin: ‘‘Eytan didn’t speak till he was five. Our parents were freaked out.’’

Eytan Kollin: ‘‘I remember not speaking. I remember all the big people around me being upset about it while I was nonchalant. I didn’t need to talk. I had an older brother and older sister who understood everything I needed, a big plushy play animal, and food; why did I need words? When other people were talking, I understood what I needed to.

‘‘I didn’t read a word till I was eight – that really freaked them out! The school system completely failed. My sister taught me to read, with the nightmarish application of a ruler and the ‘See Dick and Jane’ book. To this day, Stephen King and V.C. Andrews don’t scare me at all, but ‘The ball, the big red ball, the big red bouncing ball’ scares the living shit out of me.’’

‘‘I didn’t read a word till I was eight – that really freaked them out! The school system completely failed. My sister taught me to read, with the nightmarish application of a ruler and the ‘See Dick and Jane’ book. To this day, Stephen King and V.C. Andrews don’t scare me at all, but ‘The ball, the big red ball, the big red bouncing ball’ scares the living shit out of me.’’

DK: ‘‘Because Eytan didn’t speak until later and didn’t start writing and all of that, within the social circles of schools he was marginalized. Because of that, he would just go to the library and read. He spent years, much earlier than most kids would, in a library, filling his head with information: reading and reading and reading….’’

…

EK: ‘‘People talk about inspiration, but what really matters is desperation. Fear of well-deserved anonymity: that’s what drives so many of us to action. I had just come off a divorce, I was living with my parents, didn’t have a job. If I’d had a garage to live in, I would have hit the perfect trifecta of failure in the United States. At bar mitzvahs and weddings, I was being put at the table with people in their 30s who live with their parents. I took a look around and I was like, ‘Oh. Loser.’ I went to Dani and said, ‘Do you want to write a book?’ He said no. But Dani had some of his own issues.’’

DK: ‘‘It was only when we were both broke and desperate that we decided, ‘Hey, let’s do the whole Reese’s peanut butter cup thing: chocolate and peanut butter.’ I had moved back from the Middle East at another down time in the economy, couldn’t find a job at any ad agency, and ended up living with my in-laws and three kids. So I had nothing to do while I was looking for work, and I said, ‘Let me take a look at some of these ideas, because you’re not doing anything on your own.’ (Eytan is the great unmotivator – it’s like moving a mountain to get him to do anything – but I am very anal-retentive.) So he gave me a whole folder of ideas. The Unincorporated Man was one of them, just amazing! It was like a ten-page treatment. So I said, ‘Let’s outline it.’’’

EK: ‘‘Mind you, at this point we haven’t had any writing courses, we haven’t taken any annexes. No short stories. We just decided, ‘What the heck? Let’s write a novel.’ And it was science fiction.’’

…

EK: ‘‘The initial idea came out of my job. I had been teaching in Compton: East LA, the ghetto, the slums of the slums, a lot of social discohesion. We had lockdowns on campus because there were gangs outside. But these kids I was teaching were sharp. We’d play chess, and if I wasn’t watching the board they’d beat me. I did the stock game, and I had a kid who understood the market. He just had that feel: he was able to pick stocks. But he had to have somebody read the page to him, because he was not numerate or literate. This guy, if he had been given a decent education, would have started out in the mail room of Charles Schwab or Merrill Lynch, and within ten years would have had an office – within 15 years, a corner office. But it was useless. His education had been stolen by the state.

‘‘So I was thinking, could we develop a system where these potentials are maximized? We have one and it’s called capitalism, but no one has really tried it. People always tinker with it. What if you created a capitalist system that was truly capitalist?’’

‘‘So I was thinking, could we develop a system where these potentials are maximized? We have one and it’s called capitalism, but no one has really tried it. People always tinker with it. What if you created a capitalist system that was truly capitalist?’’

DK: ‘‘As opposed to corporate socialism.’’

EK: ‘‘As opposed to the regulatory state. The great problem with capitalism is that it is completely amoral. It will kill you, me, her, anybody, in a heartbeat. It will run kiddie porn through every orifice of the Internet, if there’s a dollar to be made from it. How do you solve that problem? Then I realized the answer is relatively simple: if you make people the profit, capitalism will work just as hard for people. And the simplest way to do that is to incorporate the individual. The human becomes the corporation, not the corporation getting human attributes.

‘‘I honestly believe that capitalism – unfettered – is the best thing for humanity, but if you truly achieved it humanity would find some way to screw it up. People want power, dominion, to impose their will on others. We’re inventive, creative, kind, generous. We’re busybodies, we’re demanding, we’re sure that we’re right and the other person is wrong. We want to impose our beliefs. So no matter what system you have, eventually it will fall apart.’’

…

DK: ‘‘Now that we’ve finished the sequels, we’re writing an unrelated novel, Father Figure, in which women essentially run the world and men know their place. It will be an alternate history, breakpoint 1918. You’re still in a sort of Victorian era, and then it pushes forward with women running everything. What’s that going to look like governmentally, technologically, sociologically? Compared to the history of men running the world, it’s a much better world.’’

Excerpts from the interview:

Excerpts from the interview:

I wish science fiction wasn’t infested with “libertarian” sh*theads.

Pingback:SF Signal: SF Tidbits for 4/22/11

Pingback:SF Signal: SF Tidbits for 4/23/11