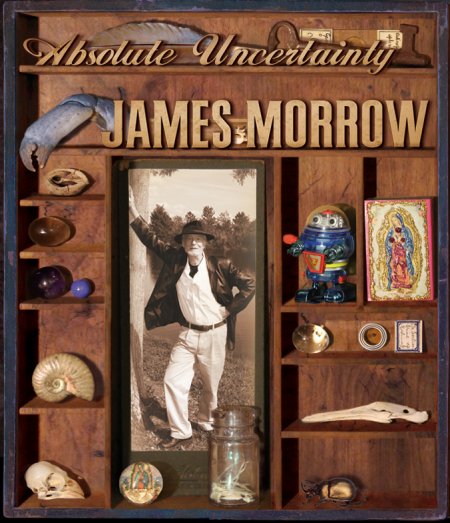

James Morrow: Absolute Uncertainty

James Kenneth Morrow was born March 17, 1947, in Philadelphia PA and received a BA in creative writing from the University of Pennsylvania in 1969. He earned an MAT from Harvard in 1970, taught English at the Cambridge Pilot School from 1970-71, worked as an instructional materials specialist for the Chelmsford Public Schools in Massachusetts from 1972-74, taught media production at Tufts University from 1977-79, and contributed articles to A Teacher’s Guide to NOVA from 1979-85. He has been mostly a freelance writer for nearly 40 years. He has two children from his first marriage (to Jean Pierce) and lives in State College PA with second wife Kathryn Smith Morrow and son Christopher.

James Kenneth Morrow was born March 17, 1947, in Philadelphia PA and received a BA in creative writing from the University of Pennsylvania in 1969. He earned an MAT from Harvard in 1970, taught English at the Cambridge Pilot School from 1970-71, worked as an instructional materials specialist for the Chelmsford Public Schools in Massachusetts from 1972-74, taught media production at Tufts University from 1977-79, and contributed articles to A Teacher’s Guide to NOVA from 1979-85. He has been mostly a freelance writer for nearly 40 years. He has two children from his first marriage (to Jean Pierce) and lives in State College PA with second wife Kathryn Smith Morrow and son Christopher.

Morrow is one of our leading satirists. His first novel, The Wine of Violence, appeared in 1981, followed by The Continent of Lies (1985); Nebula Award finalist and Campbell Memorial Award runner-up This Is the Way the World Ends (1986); and World Fantasy Award Winner Only Begotten Daughter (1990), also a Campbell Memorial and Nebula Award finalist. His Godhead trilogy includes the World Fantasy and Grand Prix l’Imaginaire winner Towing Jehovah (1994), also a Hugo, Clarke, and Nebula Award finalist; New York Times notable book Blameless in Abaddon (1996); and Grand Prix l’Imaginaire finalist The Eternal Footman (1999). Postmodern historical epic The Last Witchfinder appeared in 2006, and Frankenstein homage, The Philosopher’s Apprentice, in 2008. His latest novel is Galápagos Regained (2015).

Morrow is equally adept at short fiction. Notable stories include Nebula Award winners ‘‘Bible Stories for Adults #17: The Deluge’’ (1989) and novella City of Truth (1990), and Nebula Award nominee ‘‘Auspicious Eggs’’ (2000). Novella Shambling Towards Hiroshima (2009) won the Theodore Sturgeon Memorial Award and was a Hugo and Nebula Award finalist. Novella The Madonna and the Starship appeared in 2014. His stories have been collected in Author’s Choice Monthly Issue 8 (1990), World Fantasy Award nominee Bible Stories for Adults (1996), and The Cat’s Pajamas & Other Stories (2004). Collection Reality By Other Means is forthcoming.

Morrow edited the Nebula Awards anthologies numbers 26, 27, and 28 (1993-1994), and co-edited The SFWA European Hall of Fame (2008, with Kathryn Morrow). He won a Prix Utopia Award for life achievement at the Utopiales Festival in Nantes, France, in 2005.

Excerpts from the interview:

‘‘I’m a difficult writer to categorize. If it said ‘science fiction author’ on my tombstone, I’d be happy in my state of oblivion. If it said ‘satirist’ on my tombstone, I’d be equally satisfied. I think the river of my imagination is fed by all the tributaries of the satiric tradition, but I appreciate the particular ways the science fiction toolkit lets me deconstruct human follies and foibles. My literary heroes certainly include SF satirists like Robert Sheckley and William Tenn, but also mainstream satirists. Jonathan Swift is a name I don’t get tired of hearing associated with the oeuvre of James Morrow. Voltaire, certainly, and Mark Twain, and Joseph Heller. I’ve drawn nourishment from all their work.”

…

‘‘I hope I never lose my edge. If I ever become some kind of benevolent grandfather figure – God strike me down! I always want to make people nervous. I insist that people get up every morning and do an uncomfortable amount of thinking. That’s the great gift of the 18th-century Enlightenment, that insistence on a conversation that must never stop, a conversation that must never be shut down by theistic fantasies about the workings of the universe. Absolute certainty is the great malaise of our species, all those clerics and political thinkers who say, ‘Please ignore this pile of bodies over here while I tell you how the world works.’

‘‘When you’re a satirist, nothing is sacred, not even worldviews you happen to agree with. One thing I like about my Towing Jehovah thought experiment, one of the surprising inevitabilities that precipitated out of that broth, was that it gave me an opportunity to mock myself. At the center of the novel is the conceit of the Corpus Dei, the two-mile-long corpse of God that my hero, a supertanker captain, must deliver to its final resting place in the Arctic. As the plot unfolds, the body becomes a sort of three-dimensional Rorschach test, a big floating inkblot. That novel is a bit like the Hindu fable of the Blind Men and the Elephant: everyone comes away with a different interpretation. You touch the elephant’s tusk, and you decide an elephant is like a spear. The leg of the elephant leads one blind man to believe an elephant is essentially a tree, and the tail means elephants are ropes, and the trunk means elephants are snakes.

‘‘In Towing Jehovah, one of those limited viewpoints becomes that of atheists, even though I’m an atheist myself. When you think about it, if you stumble upon the corpse of God, that means that he or she or it was once alive, and that invalidates the atheist argument. I had fun making up the Central Park West Enlightenment League, and being rather severe with them for wanting to blow the Corpus Dei out of the water. It’s a very human reaction, but pretty hypocritical. One of the more clear-thinking Enlightenment League members accuses her fellow skeptics of what she calls ‘atheist fundamentalism’ – so long before the New Atheist movement, I anticipated the problem of doctrinaire secularism.

‘‘It’s funny, though. Now that the notion of ‘atheist fundamentalism’ has become so common – I think of the pleasure public intellectuals like Chris Hedges and Terry Eagleton take in sneering at Richard Dawkins and Sam Harris – now that ‘atheist fundamentalism’ is such a popular term, I find myself pushing back against it. It seems to me that most of Dawkins’s detractors are sort of like the courtiers in the Hans Christian Andersen fable, who can’t bring themselves to admit the emperor is naked. I can imagine a sequel in which, after the little boy blurts out the truth during the parade, the courtiers start attacking him: ‘You know, that little boy is awfully ugly.’ ‘I heard his parents never got married.’ ‘That cheeky kid – who is he to talk about nakedness? He has no advanced degree in the ontology of nakedness!’ It seems to me that most critiques of the New Atheists never get beyond that level of discourse.”

…

‘‘Although I’m an atheist, I don’t really write as an atheist. I write as a heretic. I write as a bewildered pilgrim, someone who has been thrown into the world, like everybody else, and feels he has an obligation in his perplexity to ask really good questions. There’s a readership for James Morrow novels among the disciples of Christopher Hitchens and Richard Dawkins, but it’s not where I live. I live in the world of theological and philosophical discourse. That’s where the action is. I’ll always enjoy sharing a beer with someone who’s obsessed with God’s nonexistence, but I’d also love to drink with a Jesuit priest who’s willing to wrestle with the theistic argument and its manifest limitations. That is not to say I’m becoming sympathetic to religion. Whenever I hear the word ‘spiritual’ in a sentence, I know that nothing good or interesting is about to follow. And yet, I must admit that if it weren’t for religion, I’d be out of a job.”

…

‘‘Galápagos Regained came about because I’d had some commercial success with The Last Witchfinder, my attempt to dramatize the birth of the scientific worldview. I thought a follow-up historical epic would be a good idea, but I couldn’t think of a premise. My wife, Kathy, had to live with my distress, and one day she turned to me and said, ‘Jim, ever since I’ve known you, you’ve been bending my ear about Charles Darwin. The solution has been staring us in the face.’ My enthusiasm for Darwin goes back to my reading of Robert Ardrey’s African Genesis in college. Nobody reads that book today, and its killer-ape theory now seems overwrought and maybe misogynist – but I responded to Ardrey’s rhapsodizing about our intimate connection to the animal world. Many kids of my generation weren’t formally taught about Darwin in school. In one of his essays Stephen Jay Gould makes the point that William Jennings Bryan and his fellow fundamentalists weren’t the big losers in the Scopes trial. In the decades that followed, there was a resurgence of Evangelicalism, and a rise in textbook censorship. When I took biology in ninth grade, not a word was said about the theory of evolution, the Tree of Life, or the insights of Darwin. It was all about taxonomy.”

…

‘‘Next up for me – you’ll never guess – is another theological epic. The working title is Lazarus Is Waiting. Years ago I remember saying to Kathy, who’s my muse, ‘I think the conversion of the Emperor Constantine to Christianity is ripe for James Morrow’s satiric scalpel.’ Kathy said, ‘No! No! Good God, you’re going to disappear into the valley of research, and I’ll never see you again.’ But I believe I’ve figured out how to avoid dragging in a lot of actual history. The novel is going to be deliberately cartoonish, a tale told by a half-mad Lazarus who travels about on a time-traveling Egyptian ship of possibly extraterrestrial origin, so I won’t have to render every moment with complete verisimilitude.”

Read the complete interview in the June 2015 issue of Locus Magazine. Interview design by Francesca Myman.