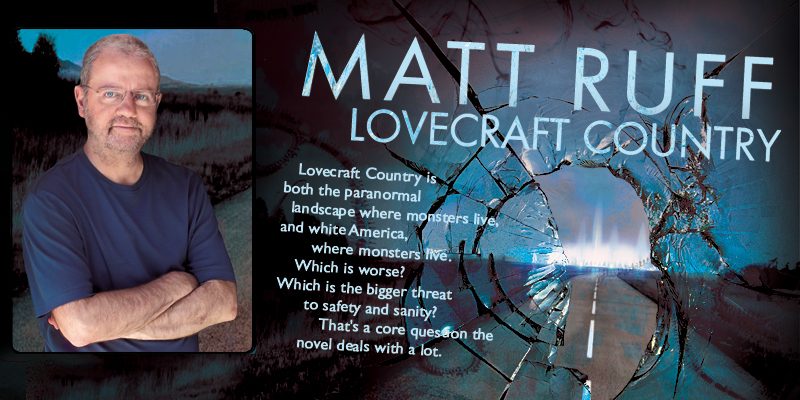

Matt Ruff: Lovecraft Country

Matthew Theron Ruff was born September 8, 1965 in New York. He attended Cornell University, where he studied English. His senior thesis became first novel Fool on the Hill (1988), a fantasy set at the college, and a Mythopoeic and Crawford Award nominee. He has been a full-time writer ever since.

Second book Sewer, Gas & Electric: The Public Works Trilogy (1997) was a satirical SF novel, and established Ruff’s pattern of never writing the same kind of novel twice. Tiptree Memorial Award winner Set This House in Order: A Romance of Souls (2003) is a literary novel about two people with multiple personalities, but has a very SFnal sensibility. Campbell Memorial Award finalist Bad Monkeys (2007) was heavily influenced by the works of Philip K. Dick. Sidewise Award finalist The Mirage (2012) is an alternate history that flips the balance of power between the US and the Middle East.

His latest book, Lovecraft Country, (currently a World Fantasy Award finalist) is a mosaic novel about a black family in the 1950s confronting supernatural terrors alongside real-life racism; it is in development as a TV series at HBO. He lives in Seattle WA with his wife Lisa Gold, married 1998.

Excerpts from the interview:

‘‘At some point I started telling people I decided to become a writer when I was five years old, but really I don’t remember – I just always wanted to do this. I don’t know if I knew the word ‘novelist’ back then, but my interest was always specifically in long-form fiction. When I was younger a lot of people still had this idea that you begin by writing short stories and work your way up to novels. But I was always naturally a long-form guy, so I basically spent my childhood and adolescence teaching myself how to do that. My early efforts as a kid were like soap operas. They didn’t have structure – I would just start telling a story until I got bored with it, and then stop and start something else.”

…

‘‘Sometime in my early teens I took a run at doing a fantasy novel and came very close to finishing it. It was a horrible amateurish Tolkien-derived thing, but it did actually have a recognizable plot. I had started to achieve almost the structure of a novel, and what finally pushed me over the edge was that my parents were both devout Lutherans – my dad a Lutheran minister and hospital chaplain, my mother a missionary’s daughter. I realized around age 14 or 15 I probably wasn’t going to stay in the church. Partly as a way of telling my parents, I wrote this novel called The Gospel According to St. Thomas, which is a somewhat autobiographical story about a Lutheran minister’s son who grapples with losing his faith. I don’t know that it was a very good book, but because it was about something I cared about, I actually finished it. That was the book that showed me I could actually do a novel-length project and get it done.

‘‘So I’d written this book to break the news to my parents about my loss of faith, but then my mom did the mom thing where she was cleaning my room and found the manuscript and read it without telling me. I had been all prepared for a big fight about me leaving the church. She just let it drop in passing, ‘I read your book, and it was pretty good.’ Nothing beyond that. I was really mad for a while. I’d built up this whole scene in my head that didn’t happen. Afterwards I thought it was just as well. The book had done its job. I got my message across, and demonstrated to myself that I could finish a project if I wanted it badly enough. From there, it was a matter of working my way up to writing a book I could actually sell.”

…

‘‘Lovecraft is interesting because if you’d asked me 30 years ago, I would have said he’s somebody whose imitators I liked better than him. I said the same thing about Phillip K. Dick for a while as well. My problem wasn’t actually the racism in Lovecraft, which I wasn’t as sensitive to when I was younger. It was there, but it was in so much other stuff too that I didn’t necessarily see it as noteworthy, if that makes sense. If you were reading a lot of science fiction and fantasy back in the ‘70s and ‘80s, there was just so much racist background noise I think you tune a lot of that out. At least, I tuned a lot of it out, and a lot of other folks who did the same get very annoyed when it’s brought to their attention now and they’re not allowed to tune it out anymore. Lovecraft’s prose style didn’t work for me, so I liked more contemporary authors who took the creepy elements and the Elder Gods, but wrote in a more modern style. Going back now, I have more of an appreciation for the way Lovecraft writes. There are things that still don’t quite work – he’ll never use one word when a dozen will do – but I can appreciate more what he got right. He gives great dread. He’s a master at building anticipation that something bad is going to happen. He’s the kind of writer that if the monster appears at all, it’s going to be in the last paragraph, so the whole thing is anticipation of the moment where everything’s going to go wrong, and you’re screaming at the characters who are choosing to put themselves in dangerous situations. At The Mountains of Madness is a perfect example. ‘Why are you messing around in these ruins, guys? You know what’s going to happen.’ That’s part of what Lovecraft gets right, and a lot of those elements work perfectly well without the racism.”

…

‘‘With Lovecraft Country, I wanted to do something kind of like The X-Files, where you have this recurring cast of characters having a series of paranormal adventures. The default with a story like that is to have it be about some sort of government agency, traditionally mostly white characters, but I wanted to open it up and do something different. I hit on this idea of instead of Mulder and Scully being white FBI agents, having it be about a black family who own a travel agency in the 1950s. The agency publishes a magazine called The Safe Negro Travel Guide, which is inspired by real travel guides like The Negro Motorist Green Book that helped black tourists find safe accommodations during the Jim Crow era.

“Starting from that premise, I wanted to take some of my favorite science fiction, fantasy, and horror tropes and see how those stories changed if you put a black character at the center. Take some people who might love science fiction themselves, but felt excluded from it like they were excluded from every other part of culture in the 1950s, and make them the stars. That was the core idea. Lovecraft came into it through the back door, because I wanted a thematic bridge between the paranormal horrors and the more mundane horrors of life in the 1950s. Lovecraft was kinda perfect for that because he was both an iconic horror writer and an outspoken white supremacist. That’s where the title came from. Lovecraft Country is both the paranormal landscape where monsters live, and white America, where monsters live. Which is worse? Which is the bigger threat to safety and sanity? That’s a core question the novel deals with a lot. The real-world horror almost always wins out. That wasn’t a huge surprise to me. What was good about it was that the dual level horror adds a richness you wouldn’t get with straight fantasy, or straight realism, alone. Having to constantly deal with these real-life hazards at least prepares the characters for the supernatural ones. It’s not like their lives haven’t been threatened before, it’s not like they haven’t found themselves in these mind-numbing situations before – it’s just the specifics are a little different this time. And, of course, my protagonists are also nerds, so they have the genre savvy to deal with ghosts and warlocks and eldritch horrors.”

…

‘‘I’m not normally a sequel guy, but this book is kind of an exception. I could do a lot more with these characters, and I think I might like to carry the story forward. That’s going to depend on how that fits in with HBO’s plans and their schedule. I’m not a fast writer, and I don’t necessarily want to end up in the position George R.R. Martin is in, where the books lag behind the TV show. I’ll have to see – I’ve got some other ideas for novels, too. At the time of this conversation, I’m still reeling from the news that the HBO series is a thing. I’ve got some time to figure out what I’m doing next.

‘‘I’ve been very lucky in my writing career in that I’ve always been able to pick my next project. I’ve always had a publishing house willing to let me go there. I’ve never been told, ‘You have to do this’ or ‘You can’t do this.’ They’ve been up for whatever. I owe a lot to Morgan Entrekin, who bought Fool on the Hill for Atlantic Monthly Press. Fool on the Hill could have been published as a straight genre novel, or as a literary novel. The initial concept cover art looked very much like a straight-up fantasy novel, but Morgan vetoed that and made them go back to the drawing board. His thinking was, ‘Fantasy fans are going to find this book no matter what it looks like, so we want a cover that’s ambiguous enough that people who think they don’t like fantasy will pick it up too.’ Some years later I was talking to Charles de Lint about this and he said, ‘You’re very lucky you didn’t get stuck with the unicorn on the cover.’ It was a very savvy marketing move, and it meant I wasn’t typecast as writing fantasy. I was able to do Sewer, Gas & Electric next, which was more science fiction satire, and then Set This House in Order, which is mainstream with a science fictional temperament, I guess. Every time I’ve been able to do what is technically a different genre, but they’re all Matt Ruff novels.’’