Lois Tilton reviews Short Fiction, late January

I’m finding a lot of good stories this time. Commendations to Asimov’s, Lady Churchill, and Beneath Ceaseless Skies.

Publications Reviewed

- Asimov’s, March 2013

- Analog, April 2013

- Lady Churchill’s Rosebud Wristlet #28, January 2013

- Beneath Ceaseless Skies, Janaury 2013

- Strange Horizons, January 2013

- Tor.com, January 2013

- Crossed Genres, January 2013

Asimov’s, March 2013

A strong issue. I’m happy to see the zine expanding its roster of authors. This, I believe, is Sanford’s second appearance here and Tidhar’s first.

“Feral Moon” by Alexander Jablokov

“The corpses fell from the interior of the moon like drops of water from an icicle.” Now, that’s a hook! It seems that the Alliance, whoever they are, is invading Phobos. The falling bodies belong to the defenders. The Alliance forces are retrieving them for later repatriation; they’re humane invaders, as invaders go. But the operation isn’t going well. The resistance is tenacious. As Alliance Preceptor, Kingsman has the authority to cancel the entire action, if he deems it necessary. Kingsman also has a past. He’s spent much of the last three years in prison in consequence of a previous disastrous, high-casualty operation, for which someone had to pay. But the authorities needed him too much to leave him there.

Kingsman, with no assigned fire cover task, had the freedom to consider contingencies. As always, that meant he spent the vast majority of his time thinking about things that never happened, and never would. To everyone else, the things that happened seemed inevitable. To him, they were only tiny slivers of actuality poking through a vast mass of unrealized possibilities, to the extent that he sometimes felt unsure of which possible future he had actually ended up in.

Well-done military SF not only delivers action, but effectively examines the value of intelligence, strategy, tactics, and command. Most importantly, it focuses on the individuals responsible for making decisions that are going to result in people being killed, as well as the factor of earning loyalty from those who have to execute the orders and put themselves in the way of getting killed doing it. It’s noteworthy that there is little argument here about the Alliance’s invasive ways, as it’s apparently using military force to bring the entire system under its control. To the characters, this appears to be a given; readers, however, may have the uneasy feeling that they are supposed to be cheering on the bad guys. The setting and scenario are entirely Real Science Fiction, with no fantastic elements. The title, by the way, refers to the fragmentation of the Phoban society, which doesn’t promote a unified stand against the invaders, who would otherwise be in a lot more trouble.

–RECOMMENDED

“Uncertainty” by Kristine Kathryn Rusch

The editorial blurb points out that this is another take on the matter of Moe Berg’s mission to assassinate Heisenberg, following Rick Wilbur’s fine piece in the April/May 2012 issue. In this case, however, the central figure is not Berg but time agent Leah Hammerschmidt, who comes to a 1943 in which the Germans have just nuked Moscow. That, however, isn’t the real problem. The problem is that the time institute can’t see past that moment; the uncertainty is too great. Things have gotten tangled. They’ve been messing with things they don’t understand.

Heisenberg himself had said it was impossible to know all of the present, so a man could not understand the future. But what he failed to acknowledge was that a person could not completely know the past either. It had branches and eddies and complications, complications that got worse with each tinker.

In contrast with the Wilbur story, which is more concerned with the outcome of the war, here the subject is time manipulation itself, the pitfalls and paradoxes thereof. Thus it becomes a Cautionary Tale. It’s interesting that we don’t really know just who these time institute people are or who they represent. We’re told that their original purpose was to prevent the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, but it now seems that everything they do has made things worse and advanced the development and deployment of atomic weapons. The Wilbur story concluded on a positive, even triumphal note, where this one is deeply pessimistic. Readers will certainly want to compare these different accounts.

“Brother Swine” by Garrett Ashley

A really bizarre premise: people who die come back home as animals, while retaining some human consciousness and identity. It seems that there has been a war, with a lot of the townsfolk going off to fight and die, so a regular procession of returnees keeps coming. Also, perhaps because of the war, whatever civilization has been in this place is deteriorating. There is no food in town, although trucks come in with supplies from time to time, less often lately. People are very hungry; Straub is concerned that his young sister may be starving. Then Etgar returns from the war as a spotted pig, instantly causing a lot of problems.

I couldn’t remember any of the neighbors ever keeping a pig. Pigs hardly ever returned to our village for fear of being held for food. The droves who wandered into nearby fields with no direction were captured and never identified. If anything were to ever happen to our supplies, to the trucks or the little patches of gardens dotting the countryside, swine would be the first to go.

There’s a line between literary absurdity and simply not making sense, and this one comes too close to the wrong side. It’s obvious from the beginning that the question will be whether the family decides to eat Etgar; adding to the decision mix is the fact that his mother was once a wolf. And of course there’s the factor that Etgar wouldn’t really be gone if killed and eaten, only changed into some other, probably more convenient form. But the scenario isn’t quite absurd enough. There is too often the suggestion that things really matter, but the whole setup isn’t realistic enough to be convincing. It’s a striking notion; it might have worked; it falls short.

“Monday’s Monk” by Jason Sanford

In a world where the wealthy have access to nanotechnology that offers near-immortality, Somchai and Tam grew up poor in the slums of Bangkok. They were in love, but Tam was ambitious and became a leader of the campaign to extend the benefits of nano to all. However, an anti-nano militia/terrorist group is taking over the countryside. Somchai had joined a village monastery, though he was never a very good monk. But since the Blues killed the abbot and the rest, he had been the only monk left. Now the militia brings him the bodies of those they have killed for possessing nano – for even thinking about possessing nano – to be ritually burned with the proper rites. Finally they bring him Tam’s body. Somchai tries to cope as a proper monk should.

If he continually poured water on her bones and gave them enough carbon—perhaps raiding the temple’s compost piles—the surviving nanotech might rebuild Tam’s body. The tiny life-like mechanisms could recreate the hands that had once held him and the lips that had kissed him and even the memories and soul which had loved him. Everything needed to recreate Tam was bound up in the nano inside her bones. If any of her nano still existed.

But instead of pulling out the bones, Somchai raked the coals over so they’d continue to burn. He couldn’t ask Tam to suffer the pains of recreation merely because he missed her.

A powerful scenario, carried by strong characters – not only Somchai but Seh Náam, the leader of the Blues, whose treatment of the monk is part reverence for his role, part cruelly taunting him with his own religious beliefs. It’s impossible for me to read of these activities without recalling the atrocities of the Khmer Rouge, who operated out of a similar fanatical zealotry. But despite the scenes of horror, this is not a horror story nor a strongly depressing one, because it accepts the point of view that both characters share – rejecting the attachment to life, embracing death as a way of escaping the pains of rebirth. As such, the conclusion is not only positive but lighthearted. It’s not a position I’m inclined to accept, but the author makes a strong case.

–RECOMMENDED

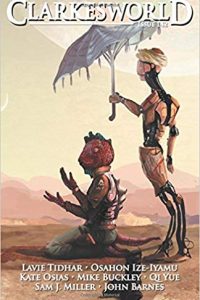

“Needlework” by Lavie Tidhar

Two hard-working young people dream of going into space, because space is now where it’s at. Those who have been there know such dreams are romantic illusions.

“We say space,” she tells him—she is feeling maudlin by then—”but we mean the opposite. Everything inside, indoors, underground, within walls. They press on you. They close and make it hard to breathe. No privacy, communal showers, toilets and the smell! They sleep in bunks, in dormitories, one on top of the other like worker ants.” She shudders.

But what young person wants to give up their romantic illusions?

It’s a welcome surprise to see Tidhar in these pages. Those unfamiliar with this talented, award-winning author should be delighted by the high level of invention and creativeness in his work, the view of an invented world crammed full of neat exotic stuff. To many US-centric readers, Tidhar’s multicultural future Earth may seem just as exotic. Others will recognize the setting from stories published elsewhere. And that’s the problem. Tidhar is lately in the habit of regifting his wonders, reprising his setting for the effect. And in pieces like this one, where the setting is primary and the story itself minimal, the feeling of “I’ve already seen all this” can grow too strong.

“Pitching Old Mars” by Michael Cassutt

In the movie sense. And that’s not a Good Thing. The author shows us how this is so.

Is there a cool sci-fi movie or story to be told that hits that conceptual sweet spot, that allows the viewer to be part of a truly alien world, much stranger than Pandora from Avatar, to see or be part of battles between warriors armed with swords and those carrying more exotic weapons on a barren landscape, with the fate of ancient empires at stake. . . ? It could be a bit like Dune or Game of Thrones, in that sense.

Analog, April 2013

This might be considered a special Edward M Lerner issue, as much of it is devoted to both the first part of a serial and a long fact article from this author. Neither of which, alas, I review here. That leaves the rest.

I’ve been anticipating this issue for a while, the first with new editor Quachri’s name on the masthead. When such a venerable institution as this zine changes leadership, there’s always a great deal of reader interest to see what changes the new guy might bring. Looking at this issue, I see a lot of the same names. I can’t judge the Lerner serial, of which we have only the first part, but the shorter fiction here is pretty lackluster. I’m hoping it represents the last leavings of the old inventory and not the new.

“Altruism, Inc” by Kyle Kirkland

Alexei Tate is a handle, which seems to be a sort of fixer in a world where just about everything seems to be negotiable and nobody does anything without a payout. It’s also a world with a lot of gene modification going on through artificial organisms called amitos, that insert new genetic material into a subject’s mitochondria. In an unlikely move, Alexei begins to investigate a company promoting altruism, headed by the woman who originally developed and patented the technique of creating amitos. Something there is fishy.

There’s a lot of stuff going on here, including some false leads and extraneous matter, but the primary Mcguffin is the genetic basis of altruism and cooperation, which seems to be disappearing from the human genetic inheritance. One question the story deals with is whether this is the reason that society has devolved to a point where no one does anything for anyone else without payment. Alexei seems to be an exception, but that doesn’t mean I’m buying his investigation of Altruism, Inc, when he has no compelling reason for doing so and when it will clearly cost him money that he can’t afford. That’s not quite the same thing as doing something for nothing. There’s also a love triangle and a certain amount of infodump about engineering mitochondrial DNA. Could use more focus.

“The Lost Bloodhound Sonata” by Carl Frederick

At some point in the future when they’ve reused the name Hurricane Ida, the storm washes a something up on the beach. The marine biology institute where Everett Fox works assigns him, an olfactory researcher, and an auditory researcher to dissect the thing – apparently having no anatomists on staff. The two men hit it off badly, as Everett correctly regards Victor as the sort of guy who’s always trying to one-up others. As the undersea creatures obviously have no vision, the scientists dispute about their means of communication. Everett suggests they might use scent; his personal research has been centered around a scent-generating device. But the rivalry between the two men complicates the issue.

Essentially, this is another love triangle. As it doesn’t hold my interest, I keep wondering about the institute that only seems to have three people on its staff, and how the scent generator could work underwater.

“The Skeptic” by Jennifer R Povey

Charles is an investigator who interviews a woman who claims to have been abducted by aliens. The odd thing is, she seems rather intelligent and well-spoken for a welfare mother, in Charles’ prejudiced opinion. At the site, he finds a communications device that might be alien, or maybe not. Of course he knows the whole thing was a hoax because there aren’t any aliens.

Not an unexpected punch line to this unsubtle story

“The Last Clone” by Brad Aiken

Famous old guy Ezekiel Kuperman hasn’t let anyone interview him in years, but somehow Blake Duncan got lucky. Why? “Because out of all the people who have asked, you’re the only one who might actually have the guts to put an end to this pathetic life of mine.” It seems this is a world where natural aging has been eliminated, except for cloned bodies. Too bad for Zeek that he transferred himself into a cloned body around a century ago, and it’s wearing out.

Talking-head story, ending in a Lesson.

“Launch Window” by Sarah Frost

Misty has come all the way into space – LaGrange Station 5 – to try to talk her sister out of leaving on the interstellar expedition. This is a clichéd piece of space boosterism: Natalia has always dreamed of the stars, Misty is plucky and brave, the villainess is of course despicable in all ways.

Lady Churchill’s Rosebud Wristlet #28, January 2013

Always happy to see a new issue of this occasional story outburst. I grope for a term to suggest the nature of the highly imaginative fiction here; “weird” will not do; “fabulist” is wrong; “odd” might fit, but I think I’ll settle on “strange”. Yes, these are strange stories, in which even experienced explorers of genre terrain may occasionally find themselves on uneven footing; there are few overworn trails here. Eight stories in just under 60 pages.

“Coffee with Count Presto” by Michael Penkas

The narrator has received a strange [yes] card of invitation, a “One Man Audience for a One Man Show” to see a magician at a local coffee house. He shows up to find that the magician, a man with a look of shabby desperation, isn’t exactly expecting him but not surprised to see him there, either. It seems that he has broken the law of the Brotherhood of Magicians by revealing his trade secrets to an outsider, and now they are coming for him.

“They want an audience. Not a big audience, but they can’t work the magic without one.” He smiled weakly. “See, I just gave away another secret.”

A moving story about a man facing the end of everything and hoping for a moment of human warmth before it comes. Short, well and simply done.

–RECOMMENDED

“Killing Curses, a Caught-Heart Quest” by Kristy Hoeppner Leahy

In a very strange [weird would also describe it] world of watersheds, which term doesn’t seem to mean what a geographer would suppose, Petech has inherited the position of curse-killer from his mother, along with her very, very weird curse-killing mouth, “interlocking pinwheeled sieves of iron and aluminum spiraled into the bones of my jaw.” By curse, we are to understand just about most things that can go wrong: jealousy, badluck, klutziness, colic, love – and apparently not cast by any particular malevolent agency – but the worst are apparently an unkillable drought and a fatal disease called mottle. Petech does his job dutifully and eventually marries Purla, a walking-tree. All is well until their daughter is born and they fall out over her upbringing, whether she will become a curse-killer.

The very imaginative fantastic setting seems to be a sparsely inhabited place, and the characters we encounter are mostly archetypes: a Quixote, a cursed Midas named Midas, a Dionysus named Tun Grier. Of these, the Quixote is most strange:

An armored knight of steely water, carrying a cirrus lance, with mad blue islands for eyes, he rode in on a horse of milky smoke, scented of coconuts and figs. He seems to be followed by an oasis of palm trees.

It is the Quixote’s quest at the heart of the plot, but the story’s heart is love and family and home.

“Notes from a Pleasant Land Where Broken Hearts Are Like Broken Hands” by Kevin Waltman

The title promisingly suggests strangeness, as does the opening in which we see the Pleasants’ work defiled by the primitive Cacklers, flinging shit all over it. But it very soon becomes clear that we’re in a standard dystopian metaphor for corporate feudalism. Disappointing.

“Akashiyaki (Octopus dumplings, serves two)” by Erica Hildebrand

Kento is following the octopus that escaped from the tank in his brother’s restaurant. It leads him into an arcade where they play skee ball and the octopus wins a prize [actually, it cheats]. Warmhearted short piece with a nice touch of absurdity.

“Springtime for the Roofer” by Brian Baldi

While the roofer is at work, the robots spend the day playing a game of tag on the lawn below.

Who taught them?, the roofer thought. Who in the world would give them this idea of tag? Who could benefit from it?

Charming little story from six individual points of view. Tag serves here as a metaphor for all the stuff that makes life fun.

–RECOMMENDED

“Vanish Girl” by Andrea M Pawley

Science fiction. The sort of dystopian setting where the privileged live in the cities and the outcasts scavenge their trash to stay alive. People with a chip are entitled to a meal and bed in the shelters, as well as one dose of mesco a day, but Cora has been luckier than most. Not only has she found the Meta-mat, which is valuable even though she doesn’t know what it does, she’s found an invisible home, protected by cloaking technology. Problem is, an older, meaner girl has followed her there.

Would be a neat idea except that a whole field full of wind turbines would be awfully dangerous to air traffic if no one could see them. And I can’t see the invisibility advantage.

“Neighbors” by Kamila Z Miller

The narrator, whom we know as Miss Strand, was brought up in comfortable circumstances before her father was arrested for debt. Now she and her mother live in poverty, devoting all their meager resources to freeing him, while she has to watch other young people courting. There is a custom that on a certain holiday, a girl puts a decorated egg into the basket of a man who interests her. There are two men living alone in the village, and she is sort of attracted to them both.

There is no overtly fantastic element here, just a delicate story of coming of age and love.

“The Book of Judgment” by Helen Marshall

When angels are fans. Miss Austen has an angelic visitor who wants to make straight the path of her life, although affairs in heaven could use some straightening as well. One of those stories that rests on a revelation readers can see coming a long way off.

Beneath Ceaseless Skies #112-113, Janaury 2013

The settings of all the stories here are quite intriguing, but I prefer the stories in issue #113, full of fantastic intrigue, love, and both featuring characters with an ambiguous degree of sexual ambiguity.

#112

“Death Sent” by Christian K Martinez

On a world once inhabited by humans and two different sentient races, the others have turned on humanity in a vast campaign of extermination. There is no explanation to be found here, only death and the messengers that carry the souls of the dead to wherever they go. And Mandate, who woke up one day and found himself become death.

He’d woken with their names on his tongue, all one million four-hundred and two of them. He’d screamed them out in a single teeth-cracking sound that drove him halfway to standing, hands carved wretchedly into claw-like shapes. Mudra. His first mudra.

A lot of imaginative scenes here in this short piece, neat images. But there is no why or how, no hint of who Mandate is that he finds himself with this deathly power. Readers who want to know what’s going on will be left without answers.

“The Stone Oaks” by Stephen Case

Claire is a novice at a remote abbey which tends a grove of rare stone oaks.

I felt where the roots brushed against stone, where they had begun, over decades, to slowly crack rock and reach inward. I felt the taste of stone as it felt to the tree: tangy, metallic, something harsher than the moist soil around it. I was not sure how to tell a tree it needed stone over soil, but I did my best, focusing on the rock, trying to will the roots to bend that way, to stretch their net tighter around the stone.

A small band of knights shows up at the abbey, taking time off from the wars, but Claire suspects they have come to take the oaks or steal their secret – which has not yet been revealed to her. It turns out to be quite a secret.

An interesting and fairly original premise. I’m really only bothered by one thing – why, since Sister Mauro already knows what weight the trees will bear, does she seem so concerned they will prove too weak?

#113

“Boat in Shadows, Crossing” by Tori Truslow

In a swampy setting, Bue discovers a talent for taming the ghosts that lurk inside the timbers of houses and boats. This path leads to the canals of the city and the boats of rich merchants, and her master’s son, who wants her to help win the heart of a beautiful girl whose face has captured his heart. But Bue can recognize a ghost when she sees one.

What was it that stirred on that shining face? Bue thought she could see the hollows under Wyrisa’s cheekbones, as if her golden skin was just a thin-stretched film. Such lovely skin.

Here’s a wondrous fantastic adventure full of magical stuff, stories nested in stories, ghosts and gods and demonic boats, and doomed loves. The narrative hops and skips and turns about, casting a story-spell that lures the reader through its twisty, root-trapped canals. I’m glad to see that BCS is starting to publish longer stories in their entirety and integrity. It would have been a shame – and impossibility – to sever this one in two.

–RECOMMENDED

“Misbegotten” by Raphael Ordoñez

Elerit is a fugitive from the Asylum for the Misbegotten, which seems to mean “freaks”, now working at the carnival and trying to evade some ruthless old accomplices with unfinished business. At this, he fails.

He was passing the shooting gallery when a gangly albino caught his eye. He froze. His desire shriveled like a salted slug. The man turned, pointed the toy crossbow at him, and let off a bolt. Then he winked and went back to his game.

Elerit gives the initial impression of a hapless character, but he proves to have deep resources and strong attachment. Another well-imagined setting increases reader enjoyment.

–RECOMMENDED

Strange Horizons, January 2013

Stories of failed love, two fantasy and one SF. I prefer the SF this time.

“Selkie Stories Are for Losers” by Sonia Satamar

The nameless narrator’s mother was a selkie who left when she found the skin her husband had hidden; the narrator hasn’t gotten over this abandonment. She’s now in love with a co-worker, Mona, and they plan to run away to Colorado to escape Mona’s mother, who yearns to return to her birthplace in Egypt. Of course the narrator will also be abandoning her father, but she doesn’t dwell on this. She is also oblivious to the fact that she keeps telling selkie stories, which would make her a loser, too.

Told in short back-and-forth sections, this one is a typical SH story about love and commitment, with the selkie tale standing in as a metaphor.

“Inventory” by Carmen Maria Machado

Waiting for the epidemic to wipe out all human life, the narrator makes lists. This one is the list of everyone she’s fucked, more or less.

Next week, I will be thirty. The sand is blowing into my mouth, my hair, the center crevice of my notebook, and the sea is choppy and gray. Beyond it, I can see the cottage, a speck on the far shore. I keep thinking I can see the virus blooming on the horizon like a sunrise. I realize the world will continue to turn, even with no people on it. Maybe it will go a little faster.

Nicely written, exploring the inexplicable variety of human relationships. It seems that this would have been much the same if the epidemic hadn’t materialized.

“Dysphonia in D Minor” by Damien Walters Grintalis

In a small country where many women are born with the ability to build with their voices, Delanna and Lucia are in love when they are young.

We sang our first bridge, a marvel of twisted cables and soaring towers, when Lucia’s hair was long and I thought love was a promise of always. It wasn’t our best or our strongest, but it was the first and had passion and hope as its support. Because we were foolish, we thought it would last forever, but first songs never lasted that long, no matter how much power the notes held in the making.

But Delanna fails the test while Lucia is judged one of the strongest talents to appear in decades. They drift apart, and Lucia becomes someone Delanna can’t understand.

A story of disillusion. We never learn just why Lucia makes the choices she has; it could be self-loathing, but that isn’t clear from Delanna’s point of view. I can’t help thinking that would be the more interesting side of the story. The setting seems at first to be one of those worlds where only women live, which turns out not to be the case.

Tor.com, January 2013

As of this writing, there is only one story posted on the site, but it’s worth going there for.

“When We Were Heroes” by Daniel Abraham

Part of the collaborative Wild Cards universe, in which, in case readers are unaware, there are all too many superheroes out on the streets, many of whom are suffering from disillusion and angst. No greater familiarity with previous stories is required. Kate [aka Curveball] is still with the system but wanting some separation between her persona as an ace and her private life. When she meets a guy who doesn’t know who she was, she seizes the chance for some normality, but it’s endangered when an ace paparazzo splashes a photo of their first kiss all over the media.

The mark of a good writer is the ability to turn a cliché into a moving experience. This is what Abraham has done here with well-chosen words and phrases that render his characters as real people, complete with dirt under their fingernails. So simple, so effective:

“It’s probably not the last time it’ll happen,” she says. If it’s too hard, I understand waits at the back of her throat, but the words won’t come out.

Somewhere in Brooklyn, Tyler groans. She’s faced armies. She’s had people with guns trying to kill her. This little sound from a distant throat scares her.

The story is less about superheroes than about the pernicious cult of celebrity, which curses its subjects to lose every expectation of privacy.

Crossed Genres, January 2013

Not quite a new magazine but a restart, this one is unusual in having a monthly theme, January being Boundaries month. There are also editorial preferences in the general directions of diversity, short length and new authors. The prose tends to be pretty well-worked, at least in this issue. One of the more promising newish zines I’ve seen lately.

“Désiré” by Megan Arkenberg

In a 29th century with the tone of a millennium past, Désiré is a talented musician composer, the toast of society.

That’s Désiré for you – mad as springtime, smooth as ice and clumsy as walking on it. We tease him, saying he’s lucky he doesn’t wear a dress, he trips over the ladies’ skirts so often. But then he apologizes so wonderfully, I’ve half a mind to trip him on purpose. That clumsiness vanishes when he’s playing, though; his fingers on a violin are quick and precise. Either that, or he fits his mistakes into the music so naturally that we don’t notice them.

Then War intrudes.

From the beginning, it’s clear that this is a tragedy, as the text begins in the future of the events and shifts back, although not to the very beginning, where the secrets of Désiré’s origin are buried. The prose is quite lovely, portentous with doom. And while readers might suppose at first that these secrets are “unnatural desires”, it is quite another matter at the tragedy’s heart. This is where the boundary comes in, the line that he has crossed, that pulls him back.

It’s also quite clear that the author is employing WWI analogies in this gilded setting, from which we only have to subtract a thousand years to be right back in familiar territory: aristocrats, cavalry, opera houses, a one-handed pianist. This is the past/future that we see, but the past/future from which Désiré has come, while unseen, is still perfectly recognizable from another part of our history, more sordid. What we have here is historical fiction wearing a new costume.

“Thin Slats of Metal, Painted” by Alex Dally MacFarlane

Jess is an imaginative child who likes to measure things. She also likes to look at the images graffistists have painted on the blinds that cover the windows of empty shops; one shop has been painted with bird-people, and Jess imagines that they want to fly away.

They had bodies like people, tall and lean, clothed. Blue-grey trousers with yellow patterns – three dots in a circle, like ice cream in a yellow-rimmed bowl – billowed out around their legs and tapered at the ankle, above small black shoes. White shirts matched their tall white hats. Their arms were the same near-white as the shutters and they held them out in front of their long, grey wings.

The notion that anyone, even an imaginative child, would suppose such painted birds might be able to fly isn’t convincing here. I would think that a child who likes to measure things might be more grounded in reality. Her act is a transgression, though done out of love, not malice.

“Wander” by Rachel Bender

Schal is a captive, a valuable one, whose arcane ability to draw maps of distant terrain is useful in the Red Empire’s conquests. Schal knows she is a collaborator, aiding the enemy, but she does not resist.

And for the next two days, Schal did the bidding of the Red Emperor who had conquered her nation and taken her prisoner for her magic. She mapped the Eastern Reaches, and as her awareness sailed up the river, she found more settlements and duly plotted them. Only the buildings – no more sheep, and if the warm spark of a human’s awareness brushed against her own, she ignored it.

Readers may not despise Schal as much as she despises herself, but she can’t be considered admirable, and she lacks agency as a character. Her ability is of some interest, but it doesn’t make a story, despite the very competent prose. What is potentially of more interest is the faint possibility that she may have more agency than anyone knows, may be doing a very different kind of magic. Or, if not her, that someone out there is. But we’ll never know. Too bad.

I think you’re misreading some aspects of Sofia Samatar’s story. The selkie story isn’t a metaphor; her mother is in fact a selkie, who returns to the sea after the narrator finds her seal-skin in the attic. And the narrator seems quite aware that she has been a loser — she has lost her mother, she tells selkie stories, she lives in a selkie story, and she’s determined not to lose anything more. The irony in this is not that she doesn’t realize that she’s a loser — but that she doesn’t realize that denial can’t heal her grief, or that she seems to be struggling towards the realization that the loss that opens the story (the loss of her key chains) leads her to finding her friend Mona, and that perhaps being a loser — the kind of person who loses things (mothers, secrets, keychains) — is the only way to being the kind of person who finds friendship and love.

Pingback:Beneath Ceaseless Skies - BCS #112, #113 Reviewed at Locus Online

Right, Mely, in the story the mother was literally a selkie. But this doesn’t preclude the selkie figure also functioning as a metaphor.

Jablokov’s “Feral Moon” ilustrates a problem I increasngly have with some “quality adventure SF”: The Alliance crushes the rebels on the ragged frontier with brute military force. Is there any reason why I should invest time in reading this, instead of watching some episodes of “Firefly” again?

Ulrich – if that’s all it was about, of course not. But there’s a whole lot more to the Jablokov, including the tactical problems of effectively [rather than brutely] applying force, as well as ethical problems. Intelligent and thoughtful military SF is so infrequently found, and I consider this one a fine example.