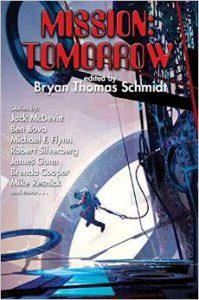

Paul Di Filippo reviews Mission: Tomorrow

Mission: Tomorrow, edited by Bryan Thomas Schmidt (Baen 978-1-4767-8094-8, $15, 336pp, trade paperback), November 2015

It seems incredible to me that the title Mission: Tomorrow has never yet been affixed to any story or book. And yet so I am told by inquiries at ISFDB and Google and Abebooks. The phrase is so quintessentially stefnal in nature, so resonant with glory and hope and possibility, those classic hallmarks of the genre, that surely it must have occurred to some writer at the dawn of the Golden Age. But apparently not. So please, hand all credit to editor Schmidt for this excellent coinage, which can serve as the uplifting obverse to Frank Herbert’s rather melancholy Destination: Void.

It seems incredible to me that the title Mission: Tomorrow has never yet been affixed to any story or book. And yet so I am told by inquiries at ISFDB and Google and Abebooks. The phrase is so quintessentially stefnal in nature, so resonant with glory and hope and possibility, those classic hallmarks of the genre, that surely it must have occurred to some writer at the dawn of the Golden Age. But apparently not. So please, hand all credit to editor Schmidt for this excellent coinage, which can serve as the uplifting obverse to Frank Herbert’s rather melancholy Destination: Void.

Next we ask, can any set of stories live up to such a perfect title? Let’s find out!

Editor Schmidt gives us a zesty, clear-eyed, charmingly brief introduction in which he lays out his remit: stories of heroic space exploration, centered mainly in our solar system. In this regard, he aligns himself with Kim Stanley Robinson’s 2312, which found plenty of slower-than-light action within our Sun’s backyard that did not contravene physics as we know it.

The first story (of nineteen), “Tombaugh Station,” by Robin Wayne Bailey, certainly delivers what’s promised. (And do I hear an echo of Wilson Tucker’s To the Tombaugh Station?) Set on Pluto, where humans have had a precarious grip for decades, it’s rife with vivid “steel beach” details and serves up a murder mystery as well. It’s followed by Jack McDevitt’s “Excalibur,” which has a day-after tomorrow setting on Earth, yet which also conjures up the rich possibilities of trans-Jovian life. Alex Shvartsman’s “The Race for Arcadia” takes us to the edges of the solar system in a one-man craft aimed at a distant exo-planet. There’s a Sturgeonesque human-interest twist to the tale which proves to be as important as the technology.

Unknown aliens have apparently retrieved that famous interplanetary NASA disc of cultural recordings known as the Golden Record, and when Aboriginal astronaut Tyrille Smith goes out in her craft to learn more, she finds herself poised on a great adventure. Such is the gist of Lezli Robyn’s “A Walkabout Amongst the Stars.” Robert Silverberg appears here courtesy of an older story unreprinted for three decades, “Sunrise on Mercury,” which finds a spaceship crew unexplainably affected by a curious Mercurian phenomenon. It’s a classic blend of Silverberg’s early journeyman conformity to sheer pulp action and his late-period examination of the darkness of the human soul.

There’s a kind of updated, au courant Planet Stories vibe to Michael Flynn’s “In Panic Town, On the Backward Moon,” and that’s pretty neat. Our working-man narrator gets involved with some criminal elements concerning a stolen artifact, on a Red Planet that has a thriving infrastructure detailed slyly and deeply. Jaleta Clegg goes into fine satirical Galaxy magazine mode with “The Ultimate Space Race,” while Christopher McKitterick offers a lyrical look at First Contact with Jovian natives that blossoms out astonishingly into transcendental realms, with “Orpheus’ Engines.” Modeling an asteroid adventure around Jules Verne’s famous globe-trotting novel, Jay Werkheiser delivers some fine suspense and thrills in “Around the NEO in Eighty Days.” And remaining amidst the asteroids, Brenda Cooper takes the great “consensus future history” trope of asteroid miner and fuses it with some Asimovian Three Laws riffs to provide several touching emotional moments in “Iron Pegasus.”

Michael Capobianco might be writing pure cyberpunk with “Airtight,” which finds a lone explorer at the mercy of corporate suits back home. Newcomer Angus McIntyre steps off brilliantly with “Windshear,” a freshly conceived look at how to inhabit the upper atmosphere of Venus. “On Edge” by Sarah Hoyt reminds me a bit of Rudy Rucker’s tales of mad inventors, as a trio of pals revolutionize space travel. Mixing the supernatural with some tough-guy noir, Mike Resnick gets his criminal antihero to a strange interplanetary ending in “Tartaros.” And David Levine extends the drone-jockey realities of the present day into the near future with “Malf,” wherein an Earth-bound asteroid threatens an unplanned descent.

The space elevator concept is utilized by Curtis Chen to suspenseful ends in “Ten Days Up,” which finds our resourceful heroine fighting to regain entrance to a GEO-destined cargo pod after being locked out in hazardous vacuum conditions. Our second and final reprint comes from the masterful James Gunn. “The Rabbit Hole” takes a crew of amateur astronauts down a white hole, with a sociodynamical tone reminiscent of Frederik Pohl or Michael Moorcock. Ben Bova gives us a look at an early incident from the life of his perennial hero Sam Gunn, as Gunn meets a Chinese taikonaut, in “Rare (Off) Earth Elements.” And Jack Skillingstead closes out the book in fine form with “Tribute,” showing us how personal resilience on Mars can triumph over bureaucratic inertia and dissolution.

The takeaway from this outstanding anthology is that even after a century of tales involving solar system exploration, writers have barely begun to scratch the surface—especially as new scientific findings offer new story parameters. Almost all of these contributions focus on The Little Guy as opposed to Great Men and Great Women of History. That’s a notable change, I think, from tracking Blackie Duquesne and the Skylark of Space around. And while traditional venues like the Asteroid Belt continue to be exploited well, newer ones such as Venus and the outer planets can support even more wide-eyed wonder.

As we face daily sobering limits on what we can currently accomplish in space, a book like this serves to keep alive the broader dreams that were so instrumental in the foundation of our genre.