Paul Di Filippo reviews Alastair Reynolds

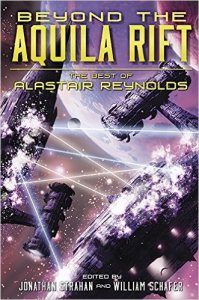

Beyond the Aquila Rift: The Best of Alastair Reynolds, edited by Jonathan Strahan & William Schafer (Subterranean 978-1596067660, $45.00, 784pp, hardcover) June 30, 2016

Some writers are associated so closely with either the novel or the short-story that it takes an effort to recall that they produced different-scale works outside their public comfort zone. Ellison and Sturgeon and Bradbury: short-story guys, though each has novels. Van Vogt and Heinlein and Clarke: novelists, although of course brilliant short-stories by all three can be adduced.

Some writers are associated so closely with either the novel or the short-story that it takes an effort to recall that they produced different-scale works outside their public comfort zone. Ellison and Sturgeon and Bradbury: short-story guys, though each has novels. Van Vogt and Heinlein and Clarke: novelists, although of course brilliant short-stories by all three can be adduced.

And so it is with Alastair Reynolds, whose massive and numerous novels surely overshadow his short fiction. But luckily for us, the perceptive editors William Schafer and Jonathan Strahan know better, and have looked more widely at the CV of Reynolds, and so they have been able to put together a collection fully as large and varied and impressive as any Reynolds opus. Eighteen entertainments, some sizable, can only be partially explicated and annotated in this particular review-space, so with that limitation in mind, off we go!

If the baseline necessity for any SF story is to have both the science and the mimetic humanity be integral to and integrated within the tale, then Reynolds’s work can stand as a prime instance of pure, archetypical SF. His novums contour and shape the human experiences and reactions within the world of his creations, and vice versa. Technology drives narrative which drives technology. It’s a satisfying feedback loop between the hearts and brains of his characters and their tools and creations.

Bruce Sterling’s classic Schismatrix can be seen as a seminal model for Reynolds’s Revelation Space universe, since both series deal with various competing factions of posthumans in off-Earth settings. Our first tale in this collection, “Great Wall of Mars,” is placed early in the future history, and features a wonderful Big Dumb Object, a kind of artificial terrarium on the Red Planet. Questions of ultimate loyalties and treacheries alternate with plenty of action. Next up is another linked story, “Weather,” whose title refers to a damaged Conjoiner woman. Set totally onboard a spaceship fleeing pirates, the story dramatizes the way in which our differing, antagonistic worldviews can separate us and yet sometimes bleed fruitfully together across all predictable barriers.

The title story is a mind-croggling one, allied to Poul Anderson’s classic Tau Zero. Humanity employs a remnant system of stargates without really comprehending how they work. And one transit goes spectacularly wrong, leading to a situation which seems bad enough—until Reynolds yanks out the rug from underneath even that dilemma in a great “conceptual breakthrough” moment.

One great facet of Reynolds’s writing is how he can take core tropes of the field and make them feel fresh and new again. “Minla’s Flowers” deals with the notion of a world doomed by cosmic forces—think of something as primal as When Worlds Collide—and how the planet’s population might be saved. Insert a visitor from a more advanced civilization facing an impossible rescue mission, and you have the recipe for a tragedy, which Reynolds twists in unpredictable ways. Echoes of the disillusioned yet eternally questing romanticism of Roger Zelazny crop up here.

In his revelatory endnotes, the author mentions his preoccupation with art and artists, and “Zima Blue” is one of the entries in that category, showing us the career of a creator whose mysterious origins conceal a life-altering secret. Jumping to a totally different scenario—an interstellar empire some 32,000 years old—“Fury” looks at the interplay between a loyal robot servant and his posthuman master. Allusions to the Kuttner-Moore novel of the same name might just be intentional.

“The Star Surgeon’s Apprentice” is pure Keith-Laumer-style action, as a man forced to flee a planet finds himself as reluctant protégé to an amoral ship’s surgeon named, perfectly, Dr. Zeal. And after so many shiny technophile venues, “The Sledge-Maker’s Daughter” is a rousing contrast, almost like a medievalist fantasy set on a post-apocalyptic Earth.

The notion of an Indiana-Jones-style exploration of a place called “the Blood Spire” gets a gory workout in “Diamond Dogs.” On this one, Reynolds cops to being influenced by Budrys’s famous Rogue Moon, but I’d bring up Silverberg’s The Man in the Maze as another honorable ancestor. “Thousandth Night” reminded me a tad of Moorcock’s Dancers at the End of Time sequence, with its far-off unfathomable future citizens. The enigmatic spatial phenomenon known as the Matryoshka propels the events in “Troika,” as the one man who survived contact with the anomaly attempts to reconnect with those he left behind.

Resonance with The Matrix informs “Sleepover,” in which our hero is woken from suspended animation after 160 years to find a world of encapsulated humans and battling “artilects.” A sculptor who works at planetary magnitudes is the central figure in “Vainglory,” another of Reynolds’s art-centric narratives. “Trauma Pod” is enthralling but not as ground-breaking or ideationally challenging as the rest of the book, dealing with the future of military combat medicine.

A kind of Conradian tale of intertwined fates, “The Last Log of the Lachrimosa” finds our protagonists bound on a dangerous salvage-cum-rescue mission. With affinities to the socially engaged works of Lucius Shepard and Paolo Bacigalupi, “The Water Thief” shows us the plight of the poor and dispossessed in a near-future of ecological stresses. Podkayne of Mars: the Sequel? Not quite, but with its young female protagonist, “The Old Man and the Martian Sea” feels a little bit like that Heinlein classic. And finally, the droll first-person narrative of a sentient space probe embarked on a media tour is presented in “In Babelsberg.”

Combining the melancholy fatedness of early George R. R. Martin, as found in Dying of the Light, with the clear-eyed cosmicism of Stephen Baxter, Reynolds gives us a galaxy where the gravity of astronomical phenomena is counterbalanced by the dark energies of the human heart. This collection should stand as a cornerstone of the contemporary SF edifice, showing us exactly how to elegantly fuse those separate but overlapping magisteria.