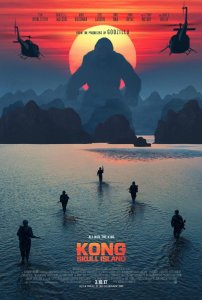

Bungle in the Jungle: A Review of Kong: Skull Island

by Gary Westfahl

by Gary Westfahl

Kong: Skull Island actually begins quite promisingly, as we are introduced to a diverse and generally appealing cast of characters, and they gather together to journey to the mysterious Skull Island and confront the enormous, and initially hostile, King Kong (also glimpsed in a prologue). One briefly imagines that director Jordan Vogt-Roberts has finally achieved what John Guillermin (in 1976) and Peter Jackson (in 2005) could not achieve – namely, a King Kong film that recaptures the charm and élan of Merian C. Cooper’s classic 1933 production. Unfortunately, the film devolves into an iterative, and increasingly unpleasant, series of variations on the two basic set pieces observed in all giant monster movies: humans vs. monster, and monster vs. monster; and the only suspense involves which character will next be dispatched to a gory demise. So, if you have ever wondered what it would look like if an enormous lizard vomited human remains, or a flock of pterodactyls started dismembering a man, this film provides the answers.

Since many elements of this film have been borrowed from its (uncredited) precursors, one’s attention is naturally focused on its innovations. Most obviously, in contrast to Guillermin and writer Lorenzo Semple, Jr.’s disastrous decision to shift the story to contemporary times, and Jackson and writers Fran Walsh and Philippa Boyens’s flawed effort to recreate its original 1930s setting, Vogt-Roberts and writers John Gatins, Dan Gilroy, Max Borenstein, and Derek Connolly have shifted the story to 1973, right at the time that the Vietnam War was ending. This provides them with the immediate advantage of appealing to that all-important aging Baby Boomer demographic by playing snippets of popular songs from the late 1960s and early 1970s, generally related in some trite fashion to the story – the Chambers Brothers’s “Time Has Come Today” (1967), Black Sabbath’s “Paranoid” (1970), Credence Clearwater Revival’s “Bad Moon Rising” (1969) and “Run Through the Jungle” (1970), and so on. (They did miss some obvious choices, though, like the Rolling Stones’s “Monkey Man” [1969] and Jethro Tull’s titularly referenced “Bungle in the Jungle” [1974].) The film even includes something for extremely elderly viewers who might have viewed the original King Kong in theatres: a few bars of Vera Lynn singing her beloved World War II ballad, “We’ll Meet Again” (1939). Older members of the audience will also appreciate the film’s hurried chronicle of American history from 1945 to 1973, conveyed by archive footage, and they will understand the significance of the Richard Nixon bobblehead in the expedition’s lead helicopter – for not only did Nixon preside over the final years of the Vietnam War, but executive Bill Randa (John Goodman), who has not told anyone that he is really seeking a monster, is also, like Nixon, engaged in a massive cover-up.

More portentously, as soldiers leaving Vietnam, led by Colonel Preston Packard (Samuel L. Jackson), are recruited to accompany Randa, scientist Houston Brooks (Corey Hawkins), tracker James Conrad (Tom Hiddleston), and photographer Mason Weaver (Brie Larson) on their expedition to Skull Island, the film can set up resonances between their ill-advised plan to conquer Kong and the United States’s ill-advised plan to conquer Vietnam. So, as discerning viewers can anticipate from the onset, and as is later spelled out in words of one syllable for non-discerning viewers, Packard will crazily come to regard killing Kong as a way to finally win his war, since misguided politicians prevented him from winning the Vietnam War. And Jackson’s character, like Colonel Miles Quaritch in Avatar (2009 – review here), becomes yet another repugnant stereotype of the military man as psychotic killer, determined to wipe out innocent residents of the natural world. To further underline its anti-colonialist message, Skull Island’s mute natives resemble Vietnamese people, and the film references Joseph Conrad’s “Heart of Darkness” (1899) by naming characters Conrad and Marlow (Conrad’s narrator) – which also recalls how Francis Ford Coppola transplanted the story to Vietnam in Apocalypse Now (1979).

To contrast with Packard’s obsessed opposition to Kong, the film hammers home the point that people need to reconcile with their enemies. Thus, when American soldier Hank Marlow (John C. Reilly) and Japanese soldier Gunpei Ikari (Miyavi) land on Skull Island at the end of World War II, they initially strive to kill each other; but we later learn that, after facing the threat of Kong, they became fast friends. Weaver, who calls herself an “anti-war photographer,” is at first prickly in the company of Conrad, whom she regards as a complicit mercenary, but they later become allies, united by their affection for Kong, and potential romantic partners (more about that later). Kong initially seems to be the visitors’ enemy, inasmuch as he (quite understandably) attacks them after they drop bombs all around him, but Randa, Brooks, Conrad, and Weaver later recognize that he is really their friend, and they even undertake to “save Kong” from Packard’s sinister machinations. (Yes, he tries to kill the ape with napalm.) Packard’s paranoid hatred of Kong is criticized when a character remarks, “Sometimes the enemy doesn’t exist until you look for one.” And the film is practicing what it preaches, since it was partially filmed in the nation that the United States once fought against, Vietnam, and as the credits reveal, provided employment for scores of Vietnamese people.

The broader question is whether these themes accord with the traditional image of King Kong, and to a large extent, they do. In earlier films, Kong on Skull Island does function as a representative of virtuous nature, properly resisting the encroachment of destructive technology, and when he is taken to New York City, breaks free of his chains, and goes on a rampage, he symbolizes people’s frustrations with the constraints of the civilized world and their occasional desire to resist its insidious limitations. In these respects, Kong might seem an ideal champion for indigenous people battling against western invaders, like the Vietnamese, and the film might be further celebrated for suggesting that such apparently intractable conflicts might be peacefully resolved – that nature and technology, King Kong and modern Americans, can peacefully coexist.

The problem is that the film later undermines its own message, as it is made clear that actually, Kong is not particularly interested in defending Skull Island and its people against technologically superior foreigners; rather, his chief goal is to defend the island against other, more predatory monsters, which ultimately marginalize Packard as the film’s principal villains. Thus, Kong becomes a symbol of good nature opposing evil nature – a dynamic that is far less evocative than good nature opposing evil civilization. The logic of the opposition is also dubious, since predators which attack other animals to consume them and stay alive are, after all, only being natural in their own way.

As to why the film would turn in this direction – well, film reviewers are always urged to avoid “spoilers,” but people who watch this film should be advised to stay and sit through the interminable end credits, because this is one of those films that offer a final, setting-up-the-sequel scene. And, since it has already been announced that the sequel to Gareth Edwards’s wretched Godzilla (2014 – review here), Godzilla: King of Monsters, will be followed by another sequel entitled Godzilla vs. Kong, one might guess that an image of Godzilla would figure in that final scene. And so it seems that American producers are setting up their own version of Toho Studios’ long-running Monster Wrestling Entertainment, Inc., with various monsters squaring off against each other for no particular reason.

Among other themes intermittently aired in the film, please don’t ask me to explain the discussions of the myth of Icarus and the fable of the lion, the mouse, and the thorn – perhaps somebody involved in one rewrite believed that literary references would add some class to the film, even if they didn’t really fit. The film, however, is more coherent in emphasizing the importance of photography: Skull Island’s existence was confirmed by satellite photographs; Packard comments that the “camera’s way more dangerous than a gun” and intimates that Weaver’s and others’ photographs helped to turn public opinion against the Vietnam War and bring it to a close; Weaver bonds with islanders by taking their photographs and allowing them to take photographs of her; this visit to Skull Island will presumably have greater effects than earlier ones because the travelers can provide photographs of what they observed; and an emotional reunion is evocatively presented in the form of a home movie. On the other hand, as one of photography’s negative impacts, the death of one character may be partially attributed to the fact that he was distracted by his camera.

While I am clearly less than enthusiastic about this film, it should be praised for finally addressing – however questionably – two logical problems at the heart of all previous King Kong films. First, how could an island large enough to be home to numerous large creatures remain unknown well into the twentieth century? The film explains that Skull Island is surrounded by a “perpetual storm” that long deterred explorers and concealed its existence until the space age. No, I am not a meteorologist, but I’m reasonably sure that “perpetual storms” do not exist in the real world; there is also the question of how some individuals in the past, like Marlow, Ikari, and Banda himself (who ultimately explains his quest for Kong as an effort to get people to believe his story about encountering him), somehow made their way to Skull Island despite this “perpetual storm.” Still, the film is at least trying to account for the island’s long obscurity.

The second problem: how could an island possibly sustain an ecosystem of enormous animals, particularly when animals isolated on islands tend to evolve toward miniaturization? We are now informed that the discredited theory of the “Hollow Earth,” which Brooks is ridiculed for reviving, is actually true: there are enormous empty spaces beneath the Earth, which happen to be inhabited by monsters, and they appear on Skull Island because there is a passageway from their underground home to the surface. Presumably, then, when Kong and his Brobdingnagian compatriots get hungry, they can always go downstairs for a snack. Of course, given that temperatures steadily rise as one goes deeper and deeper underground – a long-established fact that even Jules Verne had to explain away in offering his nineteenth century Journey to the Center of the Earth (1864) – this idea is as nonsensical as a “perpetual storm,” but again, I suppose, an idiotic explanation is better than no explanation at all. Also, some may recall that vast underground chambers were described as homes for gigantic creatures like the Mutos in Edwards’s Godzilla, leading to a startling revelation: widely described as a prequel to King Kong, Kong: Skull Island is actually a prequel to Godzilla – further explaining why it was set in 1973, twenty-six years before the Mutos were first unearthed in that film.

Any version of the Kong story must provide the ape with equally huge cohorts which inhabit his island, and the typical choices are dinosaurs and enlarged versions of modern animals. For the most part, this film’s creatures are typical, such as the aforementioned pterodactyls, a Kong-sized octopus, and the inevitable giant spider. But there are also a few novelties to report. Instead of conventional dinosaurs like tyrannosauruses or stegosauruses, the film offers strange “skullcrawlers” who resemble a hybrid of an enormous lizard and an albino human being. I don’t think they were particularly inspired creations, and one grew tired of seeing them again and again.

Still, the gigantic insect that evolved to resemble rotting logs was a nice touch; but my favorite monster was the water buffalo. Since not all animals in the real world are ferocious predators, it never seemed logical that every single one of Skull Island’s monsters would immediately attack human beings, as occurs in Jackson’s film. So, it was refreshing to have Conrad and Weaver meet up with an enormous water buffalo, which placidly observes them without making a single threatening gesture. Clearly a peaceful herbivore, he is later rescued by Weaver – and Kong – when he is trapped beneath pieces of a smashed helicopter. Instead of the film’s increasingly incessant mayhem, I would have liked to have seen more of this gentle water buffalo; perhaps, instead of employing Marlow’s makeshift boat to traverse the island, the visitors might have domesticated the water buffalo and ridden all the way on its back.

It is also interesting to observe how the film appears driven to reference iconic aspects of earlier films without really replicating them. For example, the film employs the most common name for Kong’s home, Skull Island, but never shows the huge stone skull ominously looming over the arriving travelers in the 1933 film. In the other films, Kong is always chained when he is displayed in New York, but he eventually breaks the chains to embark upon his New York adventure. Here, as the film’s title indicates, Kong never leaves Skull Island, but there does come a moment, while he is battling a skullcrawler, that Kong suddenly finds himself encumbered by chains; and to defeat the skullcrawler, he must break those chains. However, while I may have missed something, I don’t recall any explanation for the appearance of those chains. More significantly, the story of Kong traditionally involves a romantic triangle, as a handsome man and an enormous ape compete for the affections of a beautiful woman; then, when Kong demonstrates his fitness as a suitor by breaking those chains, he picks up the woman and takes her away with him. But commentators have routinely complained that a gigantic ape would never be attracted to a tiny woman, and this Kong never displays any special affection for Weaver. Still, the film feels compelled to include a scene of Kong picking up Weaver and holding her in the palm of his hand – even if it is only to rescue her from drowning.

Surprisingly, Weaver and her human suitor, Conrad, never really develop a romantic relationship either – unless one is deduced from a final, brief embrace that might simply convey that they are happy to be alive, not that they are in love. In fact, such not-quite romances may represent an emerging trend; after all, although film convention stipulates that a handsome man and beautiful woman who start working together will always fall in love, men and women in the real world now collaborate all the time without becoming an item, and filmmakers might accordingly wish to avoid having potential partners start kissing each other and talking about marriage. But they still feel obliged to provide at least a hint of the romances that audiences are anticipating. Hence, in Rogue One: A Star Wars Story (2016 – review here), the romance one expects between Jyn and Cassian never happens, though they also enjoy a final embrace; in Shin Godzilla (2016 – review here), as noted, an embryonic romance between Rando and Kayoko is only suggested; and in this film, there are similarly faint suggestions of an embryonic romance between Brooks and the scientist San (Tian Jing).

One could alternately explain all of these almost-romances by arguing that contemporary people are becoming more and more leery of making commitments; and in a different way, one could say the same about the contemporary makers of monster movies, averse to conveying any message that might offend someone. I have elsewhere discussed how the character of Godzilla has been gradually drained of all cultural significance – to become, in Edwards’s hands, a sort of attacking automaton – and while this film’s King Kong, who has figured in far fewer films, is not yet entirely devoid of meaning, Kong: Skull Island is clearly laying the groundwork for a future film that will introduce the Entirely Empty Kong. To prevent that development, one must hope that nobody sees this film, leading to the cancellation of the planned sequel(s) and allowing a new group of filmmakers, in a decade to two, to launch their own attempt to create a King Kong who is a worthy successor to the magnificent original.

Except Kong: Skull Island made huge bucks at the box office and now he and Godzilla have a shared franchise with each other. Hell, recently, Godzilla vs. Kong revitalized the theater industry.

So, kindly, get bent.