Paul Di Filippo reviews Susan Casper

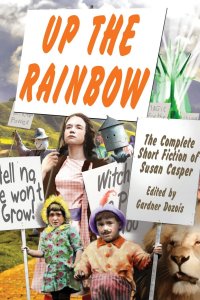

Up the Rainbow: The Complete Short Fiction of Susan Casper, edited by Gardner Dozois (Fantastic Books 978-1-5154-1028-7, $19.99, 452pp, trade paperback) July 18, 2017

Nowadays we feel, with lots of justification and pride in modern medical achievements, that seventy years old is too young to die. Yet that Biblical three-score-and-ten still looms as a numinous, even semi-uncanny milestone in anyone’s existence, a respectable span in which much can be accomplished, given luck and good circumstances, will and talent, health and ambition.

Nowadays we feel, with lots of justification and pride in modern medical achievements, that seventy years old is too young to die. Yet that Biblical three-score-and-ten still looms as a numinous, even semi-uncanny milestone in anyone’s existence, a respectable span in which much can be accomplished, given luck and good circumstances, will and talent, health and ambition.

In February of this year, after several long illnesses, we lost Susan Casper at that very age. Wife to Gardner Dozois, she was on her own merits so much more, including a talented fiction writer. It is a testament to the high regard in which she was held that this commemorative volume was so quickly assembled and issued. If, for instance, we take a case like that of R. A. Lafferty, also much beloved, who died in 2002, and who was able to receive some deserved posthumous tributes only about fifteen years later, we can see that it takes more than sheer literary worth to inspire such an outpouring so quickly.

Much of this extra-literary ambiance is evoked in a foreword by Michael Swanwick and an afterword by Andy Duncan. Both of them also offer insightful critical assessments of her work. Then come two dozen stories in chronological order of publication, with the final one seeing print here for the first time anyplace. An appendix of Casper’s non-fiction travel writings bulks out the book nicely.

I can’t go deeply into all twenty-four stories in this limited space, but will speak about some standouts in a way that I hope conveys the strengths and pleasures of Casper’s writing.

The opening three stories–her first sale was in 1983–serve almost as a mini-trilogy of horror or the Weird, showing Casper’s interest in eruptions of the uncanny into everyday life. Exemplars like Robert Bloch and Lisa Tuttle come to mind. We sense at the outset that her chosen venues will not be intergalactic space or Tolkienesque subcreations. In “Spring-Fingered Jack,” a serial killer blurs the distinctions between virtual and physical reality. “Shadowman” charts the depredations of another murderer whose undoing stems from his angering certain uncanny forces. And “Mama” reveals the supernatural lengths that a domineering matriarch will go to, in order to run (or is that “ruin?”) her daughter’s life.

Co-authored with Jack Dann and Dozois, “The Clowns” is prime Stephen King material, enlivened by sharp domestic details. A nervous young boy is the only one able to see murderous costumed jesters. Suspense is maintained at a maximum, and his fate is never certain until the very last sentence. Two entries show Casper’s dry humor, which finally surfaces, career-wise, after she has established her ability to scare. “Send No Money” concerns a supernatural, Rumplestiltskin-style bargain–delivered by a piece of talkative junk mail!–which a woman manages to turn to her advantage, while “Under Her Skin” is a short jape about a vampire with oddball tastes.

“Covenant With a Dragon” blends the quotidian albeit unsettled life of a Vietnam vet with visions from Asia that resonate with his past and motivate him to extend his compassion. The equal weight given to both spheres is typical of Casper’s self-appointed remit.

A Thorne-Smith-style body swap fills the plot of “Nine-Tenths of the Law,” while “Coming of Age” strikes a Bradburyian note in its portrait of a young girl trapped in an eerie, restrictive realm. The opening of the latter tale shows Casper’s deft hand at evoking mood and place:

The grass was still thin and brown from the heat of the summer, and the girl’s feet had left a bald patch of earth, tracing a path as she played a solitary game of ball. A few steps east—toss, catch; toss, clap, catch—and she reached the edge of the woods. A few steps west—toss, slap shoulders, catch; toss, whirl hands, catch—and she was up against the wire fence that marked the border of a neighboring farm. Her head buzzed with the chant she sang silently: A mimsy, a clapsy, I whirl my hands to bapsy… She was careful to see that her lips did not move; careful to give no outward sign.

From deep inside the shadow of the porch, Margaret could feel the eyes of the old woman upon her like a leash, pulling her back every time she neared the boundaries. Eyes that never left her, not even to check the deft needlework upon which the gnarled hands were at work. She was used to the eyes. They had been on her for thirteen years, come October. Touch my knee, touch my heel, touch my toe… As she threw the ball up into the air, the heel of her shoe caught in the stiff cotton fabric of her dress, and she fell to the ground. The ball came down on her shoulder, and bounced away. Cautiously, careful not to rip the dress, she scrambled to her feet and started chasing after the ball, then pulled up short. It had come to rest in the dead leaf-mulch just inside the edge of the forest.

A lone extraplanetary tale, “Windows of the Soul” conflates mystery and SF in good Asimovian manner, and proves that Casper could have written solid SF if she had chosen. The title story is, I believe, the longest, and has a good PJ-Farmeresque romping time while transporting Gale, the granddaughter of Dorothy of Oz, into the Emerald City, where she installs many modern notions.

And at the end, the hitherto-unseen “The Blessed Damosel” is a low-key Victorian ghost tale more concerned with evoking the contours of a woman’s lonely thwarted life than in any steampunk adventuring. There’s a feel of Le Guin to this venture.

Finally, the trip reports–a longstanding fannish tradition–reveal Casper’s zest for life, a keen observer’s eye, and a flair for journalistic concision. These travelogues show a whimsical acceptance of the world’s pleasures, with no itchy unease or greed for more than some simple relaxations in novel settings can provide.

As Swanwick has observed, Casper’s career was relatively compact: from 1983 to 2003. At that endpoint, for unexplained and perhaps ultimately inexplicable reasons, with many potential tales still at her fingertips, she ceased writing, although during her final fourteen years she still had many opportunities to do so. If one can hazard a guess as to why, based on the contents of this book, I’d say that Casper felt she had plumbed most of the rewards that writing fiction at a journeyman level could provide, and then made the decision that ramping up to master class was just not an effort she was willing to make. It’s a decision that others before her have chosen, and one that requires self-knowledge, sternness of character, and a willingness to let go of unrealistic daydreams. All qualities which the stories she did give us reveal she possessed to repletion.