Paula Guran reviews Short Fiction: May 2017

Gamut 2/17, 3/17

Apex Magazine 2/17

The Dark 4/17

Tor.com 3/8/17, 3/9/17

Uncanny 3-4/17

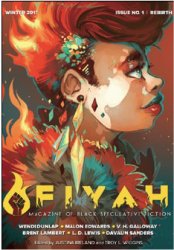

Fiyah is a new literary magazine dedicated to Black speculative fiction, a spiritual successor to the experimental FIRE!!, an African-American magazine of the Harlem Renaissance that managed only one issue in 1926. (The magazine’s offices burned to the ground shortly after it was published.) The theme of the first issue is, appropriately ‘‘rebirth.’’ Of the six stories in Fiyah #1, four are dark enough to cover here and all are strong.‘‘Revival’’ by Wendi Dunlap is set about a thousand years into the future. A band of humans have found a home on a planet they have named Revival. Serene is imprisoned and awaiting execution. Her crime is pregnancy: her fellow settlers fear she will give birth to something non-human. Although short, it packs a punch, raising questions about individual freedom, the sanctity of life, choice, and – perhaps – evolution.

Fiyah is a new literary magazine dedicated to Black speculative fiction, a spiritual successor to the experimental FIRE!!, an African-American magazine of the Harlem Renaissance that managed only one issue in 1926. (The magazine’s offices burned to the ground shortly after it was published.) The theme of the first issue is, appropriately ‘‘rebirth.’’ Of the six stories in Fiyah #1, four are dark enough to cover here and all are strong.‘‘Revival’’ by Wendi Dunlap is set about a thousand years into the future. A band of humans have found a home on a planet they have named Revival. Serene is imprisoned and awaiting execution. Her crime is pregnancy: her fellow settlers fear she will give birth to something non-human. Although short, it packs a punch, raising questions about individual freedom, the sanctity of life, choice, and – perhaps – evolution.

Truly original, ‘‘The Shade Caller’’ by DaVaun Sanders is a complex, rich tale of an outsider whose flesh is literally devoured by the sun, and strives to be accepted by the village that has taken him in. He is to be the first of his kind allowed to participate in rites that will make him Seen rather than Unseen, but on the eve of the ritual he is accused of theft. His chance to be Seen is imperiled. He sets out to prove his innocence and discovers, among other things, that: ‘‘It is a choice to acknowledge that hearing an Unseen voice does not mean one is mad.’’ This is a story of oppression and accepting not only who you are, but coming to understand there is great power in what you are.

In the disturbing ‘‘Sisi Je Kuisha (We Have Ended)’’ by V.H. Galloway, the protagonist’s father is cruelly killed, and he becomes the last of the Eloko – predatory troll-like creatures with snouts and vicious teeth who grow grass in place of hair. The introduction of guns has given humans the advantage over them. A chief’s son befriends him and saves his life. The outcome is, twice over, probably not at all what you expect.

‘‘Chesirah’’ by L.D. Lewis is less dense and outright enjoyable. Chesirah is a fenox – a being that (yes, like a phoenix) periodically burns itself to ash and is then reborn. As a safe place to burn and keep their ashes safe until they reconstitute, fenox are kept (and abused) by the eccentric rich. Chesirah wants her freedom and is not afraid to kill a master or two to gain it. Set in a spacefaring fantasy universe, the fenox’s latest bid for liberty is dependent on getting off the planet. She quickly encounters both nefarious villains who wish to thwart her and a band of potential allies. Although a complete story, one can easily see where this could be expanded into an adventurous novel.

…

Gamut is a new online magazine of ‘‘neo-noir speculative fiction with a literary bent’’ that debuted January 1. Halfway through Gamut #3, the March issue, we have ‘‘The Arrow of Time’’ by Kate Dollarhyde. In this evocative tale, the North Pole has ‘‘turned to slurry,’’ and ‘‘California shriveled under skies washed red with wildfire haze’’ more than three decades before. The nameless narrator’s scientist mother yearns for the verdant hills, blue skies, and beautiful ocean vistas of her youth, so much so that successfully she builds a time machine to go back to it. Now returned to her own era, the mother is dying of cancer. The daughter, who accepts the ‘‘hot, dry world’’ as humanity’s new home, contemplates her mother’s choices. Surreal, but grounded, the story offers the hope of adaptability amid the darkness of the changed world.

Amber Sparks’s ‘‘We Destroy the Moon’’ brims with elegant description. Sparks uses language like a surgeon’s double-edged lance, slicing and infecting at the same time. Society has broken down and in ‘‘this dry and poisoned time.’’ The narrator is an artist who creates, while her scam-artist lover makes himself into a god. ‘‘They called you a madman. They seethed, but understood – how false words were part of the new darkness. They understood how easy to become a prophet, #endtimesscamartist, how easy to sow hope among the hopeless.’’ Sparks is a unique voice whose reputation seems, so far, to have been better established in the literary world than genre.

…

Stories from Gamut #2 (February) include ‘‘Forestborn’’ by Sylvia Heike. A girl with a wild bird’s nest for hair warns the narrator that she is ‘‘forestborn’’ and cannot live in houses. It’s charming if inevitable story.

‘‘When I was fourteen, I ate a cooked piece of thigh meat off my girlfriend Sherry Wilkes.’’ One might wish to avoid a story with an opening line like that, but this is Stephen Graham Jones, so a rewarding read is guaranteed. In ‘‘Love Is A Cavity I Can’t Stop Touching’’, he indelibly examines love: not the love of a lifetime, but the all-consuming youthful passion that flashes hot and burns out quickly, and then ends with a twist creepy enough to make you shudder.

All five of these stories from Gamut are written in first person; ‘‘Figure 8’’ by Elise Tobler is told in second person. A clone – ‘‘created to kill, built… as a weapon none would suspect’’ – is ‘‘perfection’’ after seven imperfect versions who came before her. She sets out to destroy the faulty prototypes, who, despite their deficiencies, are functioning in various societal roles. The ending can be guessed early on, but the situations and deaths of the other clones are varied and interesting.

…

Apex Magazine for February offers a trio of scary stories. ‘‘Queen of Dirt’’ by Nisi Shawl features Brit, a teenager with paranormal powers, teaching children martial arts at a summer camp for city kids. Brit’s aware of some bad ‘‘entities’’ resident in the campgrounds. Despite trying to avoid them, she encounters and overcomes them. The supernatural plot parallels Brit’s feelings about her family and the conclusion ties the two elements together. There are a couple of ‘‘holes’’ in this story I wish had been better filled, but Brit’s horrific supernatural experience – her body possessed and controlled by the ‘‘other’’ – is absolutely bone chilling, and her complex teenage heroine (who previously appeared in an earlier tale) deserves more adventures. Extra points for the use of apiology both symbolically and supernaturally.

In ‘‘The Bells’’ by Lyndsie Manusos, Mary is a living doll who was once human. Owned by woodcarver Bishop, she can be ‘‘restrained and confined, played with as anyone pleased’’ and is almost emotionless except for fear, ‘‘an emotion that connects every living thing.’’ How Bishop performed a reverse Pygmalion and turned her into a doll is a mystery. The only ‘‘why’’ supplied is that she ‘‘sold her soul and lost a bet.’’ There are a couple of niggling details that distract from the excellent atmospherics Manusos provides. These flaws are not fatal, but they leave ‘‘The Bells’’ as average when it has the potential to be more.

In Rich Larson’s ‘‘You Too Shall Be Psyche’’, clan girl Reva, angry that Brete, her less-beautiful sister, has been chosen to be the bride of the God in the Pit, decides to replace her. The god turns out to be something unexpected. In fact, the whole world turns out to be something unexpected. Reva is shallow, vain, and rather stupid, so her ultimate altruistic choice seems outside her character. There are elements of old-school Clive Barker and Harlan Ellison here, with a Twilight Zone ending, which can be good or less so, depending on your taste

…

‘‘The Name, Blurry and Incomplete in His Mind’’ by Erica Mosley is one of two originals in The Dark (April). Ten-year-old Jentri – ‘‘born into a skeleton of a house and a ruin of a marriage, and learned to crawl in half-finished rooms, leaving a trail through drywall dust’’ – and her father are practically strangers, despite his weekly 90-minute visits. About the only thing they share is a ‘‘game’’ of searching the partially renovated old house for the name ‘‘Susie.’’ Scratched or written by some long-gone little girl, the ‘‘Susies’’ evolve into stories the father tells. It’s harmless – until Jentri starts seeing and feeling Susie herself. Her mother calls a halt to the game, but Susie continues to haunt. Then Jentri finds a ‘‘secret passage’’ in the house. Unfortunately, after doing an excellent job drawing the reader in and stirring up a palpable atmosphere of dread, the story turns so oblique it is difficult to interpret the conclusion.

Kristi DeMeester handles surreal spookiness very well in ‘‘The Language of Endings’’, the issue’s other original. The ghost of a 16-year-old girl – exploited, ruined, and murdered by the man who marries her – haunts and hides in his house. ‘‘He is waiting for a haunting I won’t give to him because I remember everything he hopes I’ve forgotten.’’ It’s rare that one can not only root for a wronged ghost, but enjoy her justifiable revenge. DeMeester lets us do so.

…

Tor.com’s ‘‘Come See the Living Dryad’’ by Theodora Goss is a well-told tale of a modern academic researching the murder of her great-greatgrandmother who became famous as ‘‘Daphne, the Living Dryad.’’ Displayed in freak-show fashion, the woman actually suffered from the rare Lewandowsky- Lutz dysplasia. The story is fascinating and vividly told, but as Goss pretty much reveals who the real murderer is from early on, there’s little tension or mystery.

On International Women’s Day, Tor.com published a collection of flash fiction featuring ‘‘unique visions of women inventing, playing, loving, surviving, and – of course – dreaming of themselves beyond their circumstances’’ with the theme of ‘‘Nevertheless, she persisted.’’ All are worth reading, but three of the darkest are also among the best. Both Amal El-Mohtar’s ‘‘Anabasis’’ – a story of cruel borders – and ‘‘The Ordinary Woman and the Unquiet Emperor’’ by Catherynne M. Valente – set in a kingdom where the words true and false have been banned – are heart-breaking, frightening, poetic metaphors for the very real. Seanan McGuire’s portrayal of an oppressive near-future, ‘‘Persephone’’, is more direct and perhaps even more chilling for it.

…

Most of the stories in Uncanny #15 don’t fall into my ordained territory here, but one dark fantasy should be mentioned. Beth Cato’s ‘‘With Cardamom I’ll Bind Their Lips’’ has the charm of a fairy tale: shadowy, but not completely stygian. Lady Magdalena, who uses magic to safely silence and bind ghosts so they will not interfere with the living, acquires an eager young apprentice in Vera. Times are tough and Vera, who also has the ability to speak to animals, both needs and likes the work – until an expensive accident brings Magdalena’s wrath. Vera, in an effort to make amends with Magdalena, uncovers – with the help of some animals – a mystery that could endanger her mentor. One can easily see these characters carried on in other situations.

Spring has come, bringing more light and fewer chills… but darkness lingers.

–Paula Guran