|

Interview Thread

<< | >>

| MARCH ISSUE |

-

-

Moorcock Interview

-

-

-

-

March Issue Thread

<< | >>

-

Mailing Date:

27 February 2003

|

| LOCUS MAGAZINE |

Indexes to the Magazine:

|

| |

|

|

|

|

THE MAGAZINE OF THE SCIENCE FICTION & FANTASY FIELD

|  |

|

|

|

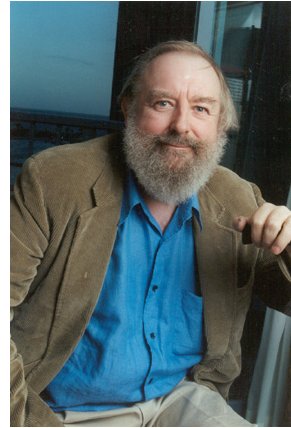

Michael Moorcock: Movements & Myths |

March 2003 |

|

Michael Moorcock is best known for a vast series of interconnected novels and stories set in the "multiverse" and concerning the Eternal Champion, a character known in various incarnations as Elric, Erekosë, Asquiol, Hawkmoon, Corum, and Von Bek: a heroic anti-hero reborn into an endless number of lives to maintain the balance of Law and Chaos. Elric novels began in 1965 with Stormbringer and include most recently The Skrayling Tree (2003); a series involving Jerry Cornelius, a modern version of Elric, began with The Final Programme in 1965 and included The Condition of Muzak (1977, winner of the Guardian Fiction Prize). Moorcock became editor of British magazine New Worlds in 1964, publishing SF and fantasy that emphasized literary values and often included experimental writing; without intending too, Moorcock and New Worlds found themselves at the center of the "New Wave" literary movement. Among Moorcock's many other works are Nebula Award-winning novella "Behold the Man" (1966), World Fantasy and John W. Campbell Award-winning Gloriana, or The Unfulfill'd Queen (1978), and literary novel Mother London, shortlisted for the Booker Prize in 1988. He lives with his wife in Austin, Texas and Majorca, Spain.

|

Photo by Charles N. Brown

Website: multiverse.org

|

Excerpts from the interview:

“That John Boorman movie Hope and Glory [1987] is actually very similar to my own life. You grow up in ruins. You grow up in a very malleable landscape that was constantly changing. Something would be gone, but at the same time that opened up vistas of new landscape, so you were constantly getting these very peculiar changes of environment. The Chaos stuff in Stormbringer is very much the way it felt, but it didn't feel weird because it's all you knew.”

*

“You get this feeling that the modern novel has become so destitute of real vitality that they're having to cast around for other genres to draw into their own. The weird thing is how you have to spell out so much more to the broad middle-class public than you do to the sharp science fiction public. I really do believe that the only useful experiment in fiction comes first in the popular media. The popular media is constantly having to solve problems of narrative for its public, so it's always having to come up with fresh ideas, fresh methods, fresh styles, fresh tones, whereas the literary novel becomes fixed in its ways. You could probably argue that Ulysses had its origins in a couple of comics that James Joyce was reading under the desk at the nunnery!”

*

“It's always good to think you've got a new movement. Judy Merril was always trying to get us to call ourselves a movement, and I wouldn't do it. We weren't a movement; we just happened to be there. Nobody who was in what they called the English New Wave had ever gone for that. You can use it now in retrospect, but we never did at the time.

“Viewing yourselves as a movement is a way of moving forward, of getting a dynamic to something and giving encouragement to people who feel they've been left out of something. Here I was, doing this kind of science fiction that I thought was great stuff. I was doing it for fun because I thought people would like it, and then I was getting these weird responses. It's like being a cat. You catch this nice big rat and you come in and dump it on the floor: 'Nice rat for supper for everybody.' And they go 'Arggh! Eww!' When I wrote the first Jerry Cornelius book, The Final Programme, Judy Merril said she thought it was an evil book and shouldn't be published. I thought I'd done this little comedy of disaster.”

*

“Arthuriana has become a genre in itself, more like TV soap opera where people think they know the characters. All that's fair enough, but it does remove the mythic power of the feminine and masculine principles. So I prefer it in its original form, even if you have to wade through Mallory's Le Morte d'Arthur -- people smashing people for pages and pages! It still has the resonances of myth about it, which makes it work for me. I don't want to know if Mordred led an unhappy childhood or not.

“Arthuriana has become a genre in itself, more like TV soap opera where people think they know the characters. All that's fair enough, but it does remove the mythic power of the feminine and masculine principles. So I prefer it in its original form, even if you have to wade through Mallory's Le Morte d'Arthur -- people smashing people for pages and pages! It still has the resonances of myth about it, which makes it work for me. I don't want to know if Mordred led an unhappy childhood or not.

“Also, most Americans tend to miss the essential matter of the stuff. Oddly, having said that, I decided to write an 'Elric' book that had some of the mythic sense of America to it. For The Skrayling Tree, I picked Longfellow and 'Hiawatha' because Longfellow's ambition had been exactly the same: to produce an American epic rather than a British epic or a Norwegian epic or whatever. He blew it at the end as the missionaries come in and Hiawatha is saying, 'Oh great! Good to see you. You're just the people we need over here.' But because of all that, I decided I wanted to do a set of myths in which the resonances came out of the stories of America. Though I don't have any serious argument with Neil Gaiman's American Gods, I believe that Americans cease to be Europeans -- the land makes them become Americans. You see it happening all the time when you travel around America.”

The full interview, with biographical profile, is published in the March 2003 issue of Locus Magazine.

|

|

|

|