Locus Magazine's Gary K. Wolfe reviews Margo Lanagan

from Locus Magazine, July 2008

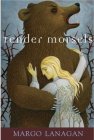

Tender Morsels, Margo Lanagan (Knopf 978-0375848117, $16.99, 448pp, hc) October 2008.

People far more knowledgeable than I (and there are more of them every day) have explained to me that the YA publishing and marketing category as we now know it largely evolved during the 1970s, then promptly claimed as its own a number of earlier classics — whether originally intended for teenagers or not — much in the way early SF anthologists decided it would be a good idea to include bits by Plato or Kepler as ersatz pedigree papers. Thus did The Catcher in the Rye and Lord of the Flies become YA mainstays, despite the dark mutterings one suspects this might have elicited from their authors. Earlier SF titles for teen readers had been called "juveniles" (as in "Heinlein juveniles," a phrase that has taken on the patina of classic craftsmanship, like Limoges china or Shaker chairs), and I suppose the YA label is no worse: SF had enough problems being regarded as "juvenile" even when not intended for juveniles, and those problems haven't entirely gone away (nor has the kind of SF that prompted this attitude). Complicating the issue further is the fact that a great deal of classic SF could easily be retrofitted into the YA fold (like Lord of the Flies or, more recently, Ender's Game), and that many if not most adult SF readers started reading these classics before they were even teenagers.

So even though YA remains one of those dumb categories named for its alleged audience rather than its characteristics (like men's adventure or chick lit), there's an argument to be made that, at least until now, it's done SF and fantasy no more harm than good: younger readers who haven't yet learned the elitist playbook, or given up reading altogether, seem to have fewer problems with the fantastic than many of their elders (by now a whole generation has grown up with Harry Potter, and four or five generations with Narnia), and SF readers — who by and large also haven't learned to be elitists, or at least aren't very good at it — are more inclined than most adults to pick up a novel labeled YA, as long as it shows some promise of meeting their genre or author expectations. And that may be true even if it's not quite a genre book, which is the case with a couple of novels we'll get to in a moment.

For now, though, here are two authors, Margo Lanagan and Neil Gaiman, for whom the YA label seems largely irrelevant, even though both of their new novels are so umbrellaed, and both, interestingly, involve children raised in sheltered circumstances who must learn to cope with the messier real world. Gaiman is, of course, the Boss, the fantasy equivalent of Springsteen if not quite Dylan, whose devoted fan base began with graphic novel readers and has continually expanded to encompass everything from gamers to movie geeks to actual literary types and guys who just like black leather jackets. In the Gaiman blogosphere, the saliva nearly drips off the screen in anticipation of The Graveyard Book. Lanagan has followed a more circuitous route; her early YA novels remain all but unknown outside of her native Australia, so that despite a career dating back to 1990 or so, she's only been discovered by most of us within the last few years — since the American publication of Black Juice in 2005, followed by the equally remarkable story collections White Time (originally published in 2000 in Australia) and Red Spikes. Those stories, in which the fantasy elements and language seem distilled to the smoky intensity of fine Armagnac, may or may not have done well among young adult readers, but they were a revelation to the rest of us, so that the widespread anticipation of her new fantasy novel Tender Morsels has very little to do with market categories. In the face of such eagerness, it's almost a relief to report that both authors have delivered on their promises.

Lanagan's Tender Morsels is perhaps best approached without any YA preconceptions, for reasons that become apparent before we're halfway through the prologue, which begins literally with a roll in the hay ("you have the kitment of a full man," explains the witch to the dwarf, "however short a stump you are the rest of you."). Long before we get to the graphic bear-fuck in Chapter 9 or the voodoo gang-rape sodomy later on, we've figured out that Lanagan shows little interest in pulling punches in the interest of perceived sensibility, and have begun to wonder if her notions of YA derive more from Thomas Hardy or D.H. Lawrence than Judy Blume. But we're also beginning to realize that the brutal intensity of the novel's more graphic bits is a necessary counterbalance to a tale that somehow manages to end on a note of almost astonishing sweetness, and that for a good part of its length takes place in a Wordsworthian bucolic idyll that is one character's notion of heaven. We first meet that character, Liga Longfield, as a 15-year-old girl in a rural, pre-industrial setting (one of those not-quite-anywhere village societies in which many of Lanagan's stories take place). Her mother has recently died, and her father has simply taken to using her as a surrogate wife, keeping her isolated and repeatedly beating and raping her, resulting in a viscerally described miscarriage and a subsequent stillbirth which he induces with the aid of powders obtained from a local witch-woman named Annie. When she tries to disguise her next pregnancy, the father returns to Annie (who by now has developed suspicions) for more potions, but is killed on the journey home, leaving Liga to give birth alone. Soon word reaches the village that a young girl is living alone in a remote cottage, and Liga is gang-raped by a posse of local youths. In despair, she decides to kill herself and her infant, but encounters a glowing, ghost-like figure who gives her two jewels and tells her to plant them by the door of her cottage.

The next morning she finds her wounds healed and the cottage magically restored. She has, we eventually learn, entered her own personal heaven, and there she raises her two daughters Branza (the result of her father's last rape) and Urdda (the result of the gang-rape). Even the local villagers, who had despised her father, become friendly and accommodating, and one of them offers to teach her needlework as a way of supporting herself. A friendly bear appears and is adopted by the family — but just as the novel seems intent on yanking us from nightmare to idyll, Lanagan unexpectedly introduces two new viewpoints, both narrated in first person. One is the dwarf Collaby Dought (who we'd met along with Annie in the prologue); the other is a village boy named Davit Ramstrong. From these we learn that it's possible to visit Liga's heaven from the real world, and, with the aid of Annie's half-baked magic, Dought uses this knowledge to amass great wealth (calling himself Lord Dought). Davit we meet as a youth participating in the village's "Bear Day" (the one invention in the novel that most resembles a Lanagan short story), in which boys dress up in bear costumes and race through the town in a bawdy inversion of Sadie Hawkins Day. Accidentally transported into Liga's world, he becomes a real bear, in fact the friendly bear that the family adopted.

Other instabilities begin to appear in Liga's world — a second bear, for example, much hornier than the first — and we learn that time passes much more slowly there than in the real world. Meanwhile, the two daughters have taken on the aspect of contrasting daughters in a Gothic novel — the innocent and fair Branza and the darker, wilder Urdda — and Urdda begins to hunger for the kind of adventures unavailable to her in this static environment, eventually making her own way into reality, where she ages far more slowly than her sister and mother. This is when the real theme of the novel begins to emerge — the balance between the brutal abuse Liga herself has suffered and the overprotectiveness of the world she has made (this is why those early unpleasant chapters are so necessary, even though it also produces the novel's one moral hiccup — Liga's "sin" is protecting her kids from a world she doesn't even know exists). With the aid of a wise sorceress named Miss Dance, Liga and her daughter are released from Liga's heaven, though to them it seems more like an exile, and Branza in particular finds it difficult to adapt to a world in which survival must be negotiated and kindness is merely a feature. By its second half, Tender Morsels begins to take on a density and moral complexity almost suggestive of a George Eliot novel, with its decades-long narrative arc, its shifting relationships, its questions involving responsibility, misdirected love, and the nature of families. Or maybe it's simply a more expansive exploration of the kinds of worlds we've glimpsed in condensed form in some of Lanagan's stories — it's certainly more leisurely in its development, and more accessible in its prose (those who find Lanagan's characteristic neologisms and swaggy narrative voices a challenge may view this with some relief, though she's still one of the few authors who could get away with a line like "she cackled ivorily"). Either way, it's a brilliant realization of a brilliant promise, and a profoundly moving tale.

Read more! This is one of three dozen books reviews from the July 2008 issue of Locus Magazine. To read more, go here to subscribe or buy the issue.

2 Comments:

I'm so glad Lanagan is poised to get more attention with her first novel as she's a terrifically talented writer with a voice that is unique. Just thinking about her short story "Singing My Sister Down" still gives me chills. But while she may be relatively unknown to the Walmart crowd, she is read and appreciated here in Lotusland, where 'Black Juice' was a finalist for the Los Angeles Times YA Book Award two years ago.

This is a great review, and very helpful for one not conversant with fantasy as a genre. Is it YA? Well, young people know more about life than I ever did at their age, but I wouldn't recommend it for under 16-17. I've posted a link to your review from my blog at http://anzlitlovers.wordpress.com.

Lisa in Oz

Post a Comment

<< Home