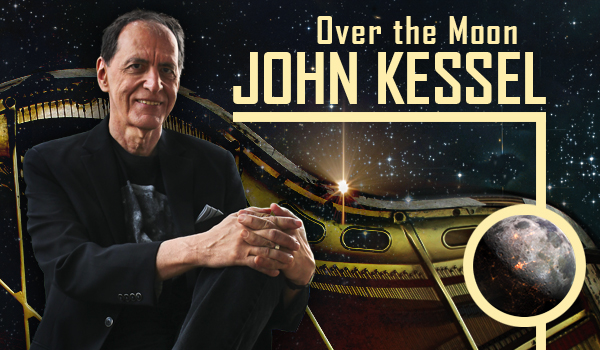

John Kessel: Over the Moon

John Joseph Vincent Kessel was born September 24, 1950 in Buffalo NY. He received a dual BA in English and Physics from the University of Rochester in 1972, an MA in English from the University of Kansas in 1974, and a PhD in English from the University of Kansas in 1981. From 1979-82 he was a copy and news editor at Commodity News Service in Kansas. In 1982 he began teaching at North Carolina State University as professor of creative writing and American literature.

Kessel’s first story appeared in 1978, but he gained prominence with Nebula Award-winning novella ‘‘Another Orphan’’ (1982). Other notable stories include Sturgeon Memorial Award winner ‘‘Buffalo’’ (1991), Tiptree Award winner ‘‘Stories for Men’’ (2002), and Shirley Jackson and Nebula Award winner ‘‘Pride and Prometheus’’ (2008). Some of his stories were collected in Meeting in Infinity (1992), The Pure Product (1997), and The Baum Plan for Financial Independence (2008).

He edited Sycamore Hill workshop anthology Intersections (1996, with Richard Butner & Mark L. Van Name), and co-edited several books with James Patrick Kelly: Feeling Very Strange (2006), Rewired (2007), The Secret History of Science Fiction (2009), Kafkaesque (2011), Nebula Awards Showcase 2012 (2012), and Digital Rapture (2012).

Debut novel Freedom Beach (1985) was co-authored with James Patrick Kelly. First solo novel Good News from Outer Space (1989) was a Campbell and Nebula Award finalist, and screwball comedy time-travel novel Corrupting Doctor Nice appeared in 1997. His latest novel The Moon and the Other (2017) further explores the world introduced in ‘‘Stories for Men’’. A novel version of Pride and Prometheus is forthcoming. Kessel lives in Raleigh NC with his wife, author Therese Anne Fowler.

Excerpts from the interview:

‘‘I have been a science fiction reader since I was a child. I had always wanted to write science fiction, but I expected to be a scientist and I studied astrophysics in college. I discovered fairly well along in my undergraduate days that I wasn’t quite up to the advanced math. I could do physics, but not well enough to be much better than a bottle washer. At the same time I also was taking English classes and I did very well in them. I had no intention to be a literature professor, but I ended up double majoring in physics and English.”

*

‘‘For a full-time academic, teaching a full course load, the academic year lends itself more easily to writing short fiction. I wrote short stories, and I enjoyed the hell out of writing short fiction. I didn’t see it as an inferior form or as a warm-up for writing novels. But the world of publishing wants novels more than it wants short stories, and I wanted to write novels, too. In the summer I would work on a novel, and the semester would start and I would have a month or so where I would keep

writing. Then the hammer would come down, and I would have so much work to do at school that I would get less writing done. It took me a long time to finish novels. My first novel, Good News from Outer Space, took me about four years to write from front to end. That doesn’t seem like so long now, but it was slow. My next one, Corrupting Dr. Nice, again took me a number of years to write. I started thinking about The Moon and the Other, a novel set in this made-up Society of Cousins lunar world, in around 1999. I wrote four proof-of-concept stories, set in the background, exploring the society and how it worked and what the different issues would be, including a novella, ‘Stories for Men’ which came out in 2002.”

*

‘‘One of the things The Moon and the Other does is explore masculinity, or what it is to be male (if there is such a thing as male). A lot of different people are reimagining that right now. What makes a person male? We have this bathroom law in North Carolina, causing endless trouble, about who gets to be in the men’s bathroom, and who gets to be in the women’s bathroom, and how you decide that. In The Moon and the Other, I wanted to present a lot of different ideas of what it is to be a man. Some of them are historical, some are notions we have today. Others are affected by the fact that it’s in the future in my invented Society of Cousins.

‘‘I think, at least historically in the United States, our ideas of masculinity have been impoverished. Where I grew up in a working-class family in Buffalo NY, the men I knew in my family, and my school, and in my life, had given to them a number of different visions – by the culture at large, by their families, by the economic system – that I believe were self-destructive. That’s still the case. The feminist movement has been tremendously helpful to men, if they’re willing to look at it and engage with it, because the potential lies there to free men from having to be what they have been. Someone said that throughout human history the vast majority of men have been a pair of hands and a strong back, and that’s it. That’s been the degree to which society and the economic system and the culture have valued them. The privileged men at the top – the ones that we write about in fantasy novels – can be other things. They can be kings, noblemen, rulers, captains of industry. The men I grew up with – my father, my uncles, my cousins – were workers. That was their value. They were at the bottom of a chain of people kicking down. It wasn’t women who were oppressing them, although I think that many men felt that way. The only people they had the right to kick were their wives and children. I don’t want to totalize that vision, but it seems to me that’s been a lot of what our culture in the West (and elsewhere) has been. I think that’s sad and destructive.”

*

‘‘I’m very happy to have The Moon and the Other out. I suspect some people may be unhappy with parts of it. As regards gender issues, I was asking as many questions as I was promoting answers. Coming from where I am, an aging white cis male heterosexual, I worry about what guys like me have to offer in exploration of gender issues. I grew up in a patriarchal culture. My mother was Sicilian and my father was Polish, both very Old World cultures. I’ve been educated by women and feminism, come from a place where I had a lot to learn. And I think I still have to learn some things.

‘‘The novel is several different kinds of books all mashed together, which is the story of my career, frankly – mashing things together, cross-breeding. In this book I wanted to make the scientific extrapolation as plausible as I could, and do social speculation, and get deeply into the characters -– tell a novel of manners, two love stories set in a made-up society –- and have political intrigues and family drama and even something of a thriller plot. I’ll let others figure out how well I carried off all these different ambitions.”

*

‘‘I’ve just turned in the final draft of a new novel, Pride and Prometheus, based on my earlier story of that title. At one point I was very self-conscious about the number of stories I’ve written that borrowed from very famous writers. ‘Another Orphan’ was a Moby-Dick story. I did a Raymond Chandler story. I wrote a sequel to Flannery O’Connor’s ‘A Good Man is Hard to Find’ and a story about Mrs. Gulliver. I imagine people saying, ‘Kessel has read too much literature and can’t come up with any of his own ideas.’ Be that as it may, it occurred to me that Pride and Prejudice was published in 1813, and Frankenstein in 1818, yet I seldom saw any discussion that put the two books together. Even though Jane Austen was older than Mary Shelley they come out of the same time period, yet they wrote very different books. In re-reading Pride and Prejudice I noticed that Darcy’s estate Pemberley is in Derbyshire, not far from the town of Matlock. In Frankenstein, which I was also teaching at the same time, Victor Frankenstein and his friend Henry are traveling through England and they stop in the town of Matlock. I thought, ‘Whoa, that was really fortuitous.’ It’s possible that characters from Pride and Prejudice could meet Victor Frankenstein without much trouble. That got me going.”

*

‘‘Most of the science fiction I write has been near future, on Earth, but I wrote a couple of space opera short stories that I enjoyed a great deal. One of them is really one of my favorite stories, ‘The Events Preceding the Helvetican Renaissance’, in The New Space Opera 2 anthology edited by Jonathan Strahan & Gardner Dozois. That one was a lot of fun to write. I loved to read that stuff when I was a kid. I thought, can I write an A.E. van Vogt story with even more spectacular bizarre stuff? I don’t want to be the old cranky guy yelling, ‘Get off my lawn’ to younger sf writers but I think a lot of them haven’t read any of these people. They don’t know Alfred Bester from A.E. van Vogt, all these writers us old timers call up as significant figures, who were just pulp writers. The whole John W. Campbell tradition doesn’t mean anything to newer writers. H.L. Gold at Galaxy, Anthony Boucher. It might as well be the ancient Phoenicians to them. Don’t get me wrong – that’s not necessarily a bad thing – it just means they’re coming at the genre from a very different place. That whole vision that Jim Gunn represented to me when I went to grad school, the idea that there were rules to write science fiction: you must extrapolate, you must have the science plausible, there must be an economic rationality to the world, the physics should work, and all that stuff. I’m enough of an old fart to miss those things. In some ways the pulp magazines and Campbell and the writers who came after, reacting against him, they made their own culture, because the world of literature was closed off to them – they had no access to it, they were never going to be recognized. They made their own rules. It was a ghetto culture, but it had a vigor, where they didn’t have to worry about Edmund Wilson coming in to tell them what was right and wrong. Edmund Wilson couldn’t be bothered. So they made their own rules, their own literature, their canon, a framework for how things should be done, which sustained them and created interesting work. That fiction is valuable, because it isn’t cued into the mainstream of American modernism and postwar Jewish fiction and all of the other stuff that was considered serious writing in America for the mid-20th century. Many of those writers took a kind of pride in the fact that they were not highbrows, they were working men in the trenches. When I think about the short stories of C.M. Kornbluth, or Damon Knight, or Cordwainer Smith, there’s value there that I hope will be remembered.”